- Exploring the Fascinating History of Cinema

- Pioneers of Cinema: Knowing Legendary Filmmakers

- A Comprehensive Guide to Genres of Films in 2024

History of Cinema: Introduction

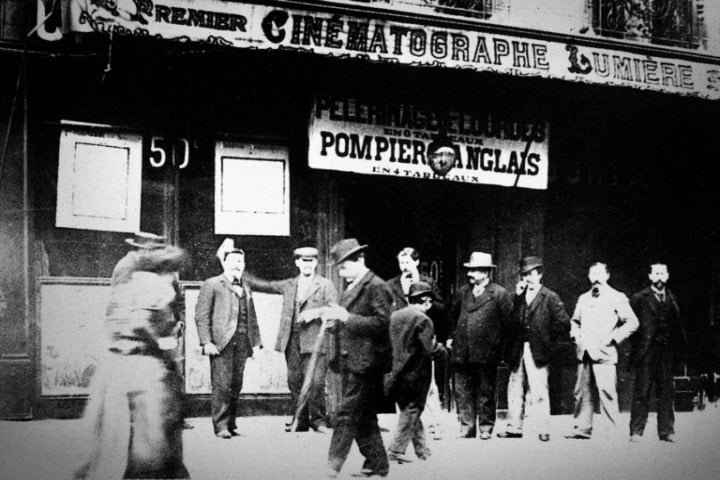

‘Cinema’ is derived from the French word ‘cinématographe,’ which means ‘motion picture projector and camera.’ The Lumiere brothers, credited with inventing the art form, coined the term in the 1890s. Since then, we have come a long way in capturing and viewing motion pictures.

In This Article

From the Lumiere brothers’ early motion-picture camera and projector called the ‘Cinématographe’ to filming short films on our cell phones, emailing them to our friends, and projecting them on our TV, we have witnessed a significant evolution in this field.

Cinema is also known as the filmmaking process or the facility where films are shown.

Theatre is similar to cinema; it can mean the facility where movies are shown or, more generally, the industry of live performances (i.e., plays, musicals, etc.).

Movies are a shortened form of a moving picture in the cinematographic sense.

Film is a medium used to record motion pictures. Films are more than flashing images on the screen; they are an art form that becomes larger than life.

Talkies were used to differentiate between silent movies and movies with sound.

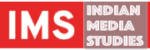

The Horse in Motion Experiment

In 1878, an Englishman, Edward Muybridge, made a bet of $25,000. He argued that a galloping horse had all four feet off the ground simultaneously. Others disagreed, saying it wasn’t possible to see this because galloping horses move too quickly.

To prove his point, Muybridge conducted an experiment that involved photographing horses in motion. Twelve cameras were set up along a track with strings attached to the shutters to capture movement in photography. As the horse ran down the track, the strings were tripped, triggering the shutters to take pictures. A series of photos were taken quickly of a horse in motion.

After the pictures were developed, it was discovered that the horse had indeed lifted all four feet off the ground for a fraction of a second. This provided conclusive proof to settle the argument once and for all.

Muybridge’s work was groundbreaking, as it helped to advance the study of motion and laid the foundation for the development of motion pictures.

This experiment discovered that the illusion of motion can be created when a series of still images of a moving object is viewed at a certain speed. When the images of a horse were presented sequentially at 0.1-second intervals, they created the illusion of continuous motion.

Persistence of Vision

When we see an image, our eyes hold it for a split second, even after it is no longer in view. This is called the persistence of vision. The human eye retains a visual impression for about 1/20th of a second after we stop looking at an object.

Because of this phenomenon, successive images merge into a single image as our eyes hold one image long enough for the next to take its place.

The human eye and brain can only process about 12 separate images per second, retaining an image for 1/16 of a second. An illusion of continuity is created if a subsequent image is replaced during this time frame.

The principle of persistence of vision is utilized in creating movies and animated films, which consist of a sequence of individual pictures presented on the screen at a rate of 24 per second. When we watch a movie, the images on our retina merge with each other to create the illusion of motion.

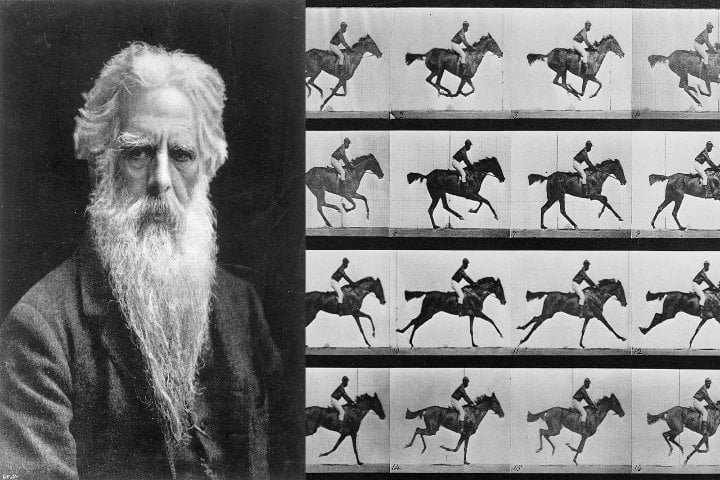

Invention of Celluloid

In 1887, Hannibal Goodwin invented a transparent and elastic film base called celluloid. This invention paved the way for creating long strips of film that could capture a series of still pictures in rapid succession.

Over time, cameras and projectors were developed that could produce 16 frames per second (FPS), and eventually, this rate was increased to 24 frames per second. Later on, George Eastman standardized film widths for cameras and projectors to 16 and 35 mm.

Beginning of Motion Picture

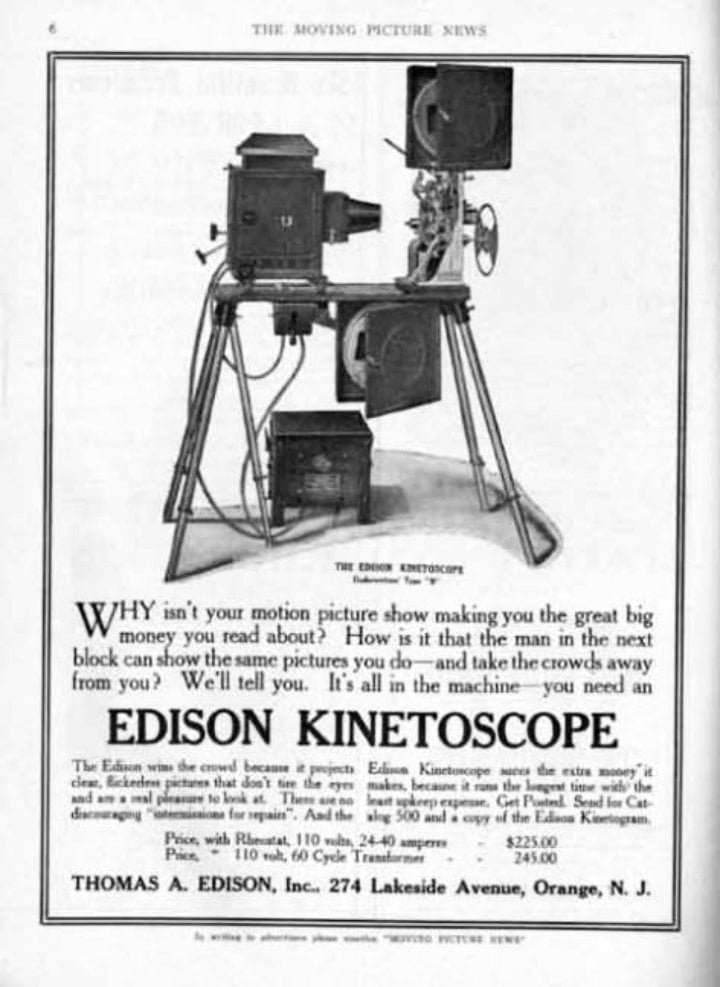

A number of devices from the past were made to entertain users with moving pictures. These devices were quite popular among people who wanted to experience the magic of animation and photography. However, there was one restriction: only one person could use each of these devices at once.

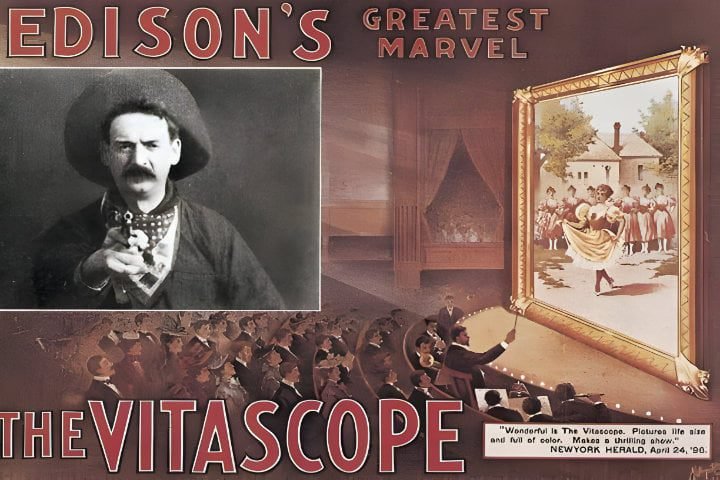

Popular devices of this kind included zoetropes, flip books, and praxinoscopes. Most popular among them were ‘kinetophones, a kinetoscope with phonographs inside their cabinets’—offered by The Edison Company in 1895. It attempted to unite sight and sound through ‘talking’ motion pictures.

The viewer would look into the peep-holes of the kinetoscope to watch a rapid sequence of drawings or photos while listening to the accompanying phonograph through two rubber ear tubes connected to the machine. The picture and sound were synchronized by connecting the two with a belt.

These simple yet innovative devices create the illusion of motion by manipulating a series of still images. Despite their flaws, people of all ages appreciated and used these devices, which were considered a marvel of technology and a source of endless fascination.

In 1913, a different version of the kinetophone was introduced to the public. This time, the sound synchronized with a motion picture projected onto a screen.

Edison’s profits were not generated from exhibiting his inventions to the general public. Instead, the revenue came from the sale of machines and prints. Edison believed selling one machine to each viewer was more desirable than having a hundred viewers crowd around one machine.

Edison misjudged how the market was going to develop. He thought the money was in the kinetograph and the kinetoscope; he didn’t think people would want to sit in the audience to see an image on a screen.

This turned out to be a major miscalculation. According to popular belief, the Lumière brothers in France first did what Edison didn’t want to do—create a projector that could show motion pictures on a screen for an audience. They called it the Cinematographe.

The Lumiere Cinematographe

In 1895, the Lumieres shot a series of 30 to 60-second films that they showed in a Paris cafe and charged a one-franc admission to see. These films covered such fascinating topics as a man falling off a horse and a child trying to catch a fish in a fishbowl.

While the Lumière films were “actualities” shot outdoors on location, Edison’s films featured circus or vaudeville acts that were shot in a small studio before a stationary camera. In both cases, the films were composed of a single unedited shot with little or no narrative content.

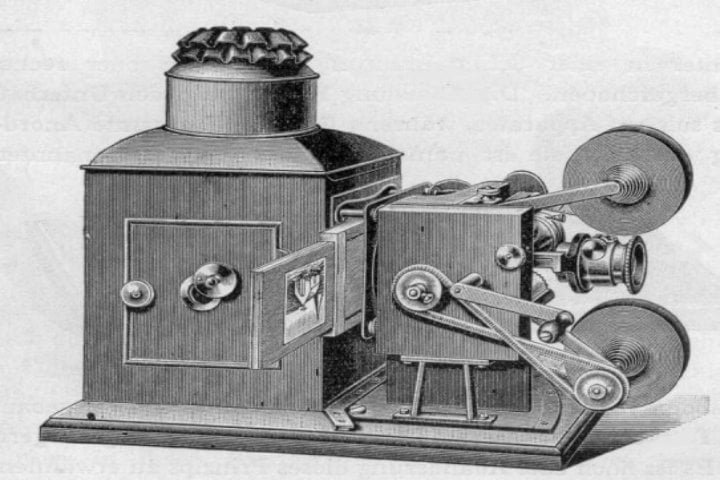

The Movie Machines

Meanwhile, numerous inventors worldwide introduced their own ‘movie machines.’ In fact, so many motion picture devices appeared at about the same time that no one person can truly be credited with the invention.

In various parts of Europe, alternative versions of the Kinetoscope began to emerge. These new inventions expanded the display of films beyond the Kinetoscope’s box and allowed for group viewings.

Devices like the Auguste and Louis Lumière cinematograph, the Robert William Paul and Birt Acres film projector, Max and Emil Skladnowsky’s “Bioscop,” Edison’s Vitoscope, and Eugene Lauste’s Eidoloscope made this possible. All of these were introduced to the public in the year 1895.

The birth of motion picture theatres coincided with the increasing popularity and length of films. These theatres consisted of a small room with wooden benches, and films had to be changed frequently as their demand increased.

During the early 1900s, the film studios, also known as ‘film factories’, located primarily in New York and New Jersey, had to produce a large number of films to meet the demand.

Beginning of Editing

In the early days, film action was continuous and uninterrupted. The idea of cutting from one scene to another was not very practical for a director on a tight schedule. The concept of editing was born out of an accident when, due to a camera malfunction, a scene was lost, and there wasn’t time to shoot it all over again. To maintain the schedule, the director left out the missing footage.

After viewing the mistake, it was concluded that the ‘lost’ footage wasn’t really necessary, and the jump in action speeded things along. By the late 1900s, it was accepted practice to stop and reposition the camera and cut directly to a different scene to tell a story.

An Early Epic: The Great Train Robbery

In 1903, Edwin S. Porter, an employee of Thomas Edison, shot the first narrative film, The Great Train Robbery. The film featured a dramatic storyline, cross-cutting between locations and camera angles. It had 14 scenes and lasted 12 minutes, making it the epic of its day. This movie was such a success among urban audiences that a movie craze was started.

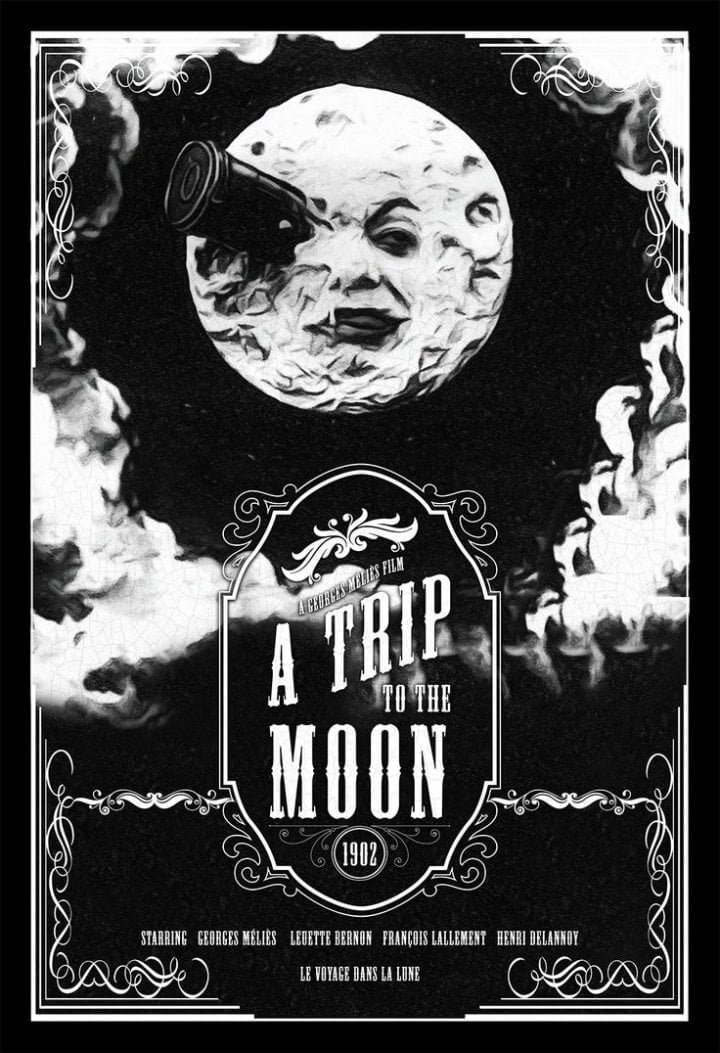

Porter “borrowed” some of his ideas from a French filmmaker, Georges Méliès, credited with virtually inventing special effects with his film Trip to the Moon in 1902.

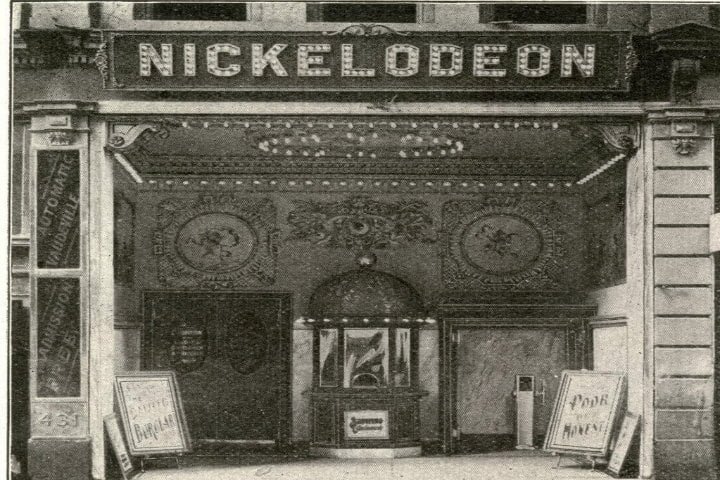

The Birth of the Nickelodeons

Nickelodeons were small theaters with a seating capacity of usually under 200. They showed 12–18 films a day, 7 days a week, and operated under an amusement license.

Most viewers were young immigrants with little or no knowledge of English, but the universal language of cinema appealed easily to them. They used to charge a nickel for admission and thus got the name Nickelodeons. By 1909, close to 8,000 nickelodeons were opened across the country.

Developments in Cinematic Narration

The following are the key developments that have influenced the evolution of cinema:

Closer Shots: Redefining Perspectives

After 1907, filmmakers significantly changed cinematography by moving the camera closer to the subjects, within a distance of 9 feet. This allowed for a better capture of nuanced expressions and emotions, resulting in a stronger connection between the audience and the characters on screen.

The Point of View (POV)

POV shots revolutionized filmmaking by letting the viewer see the story through the eyes of the character. This technique brought the audience a new level of emotional involvement and empathy. Filmmakers could tell their stories in new ways, creating a more immersive experience for the viewer.

The use of Cross-Cutting

Filmmakers started using cross-cutting techniques in their narratives. It involved quickly showing multiple scenes or storylines. This creates tension and momentum, making the film’s narrative more dramatic.

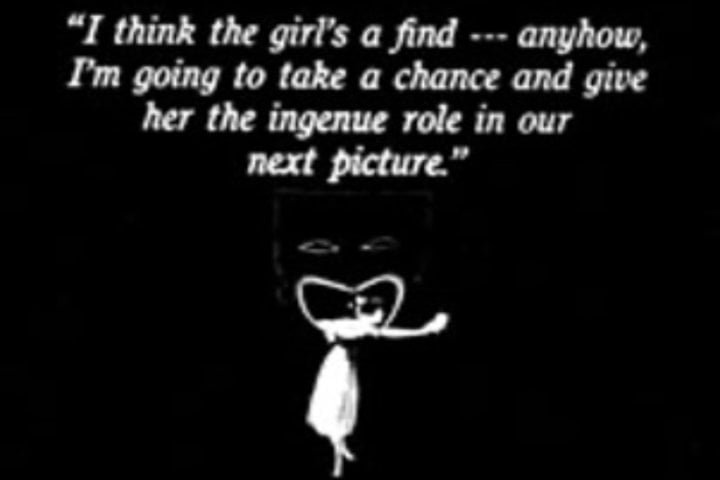

Intertitles

Using intertitles, filmmakers seamlessly integrated written text into the visual narrative, making it easier for viewers to follow the story. With this technique, language barriers are overcome, and audiences were better able to appreciate the story being told.

Dialogue on Screens

The introduction of written dialogue on screens between shots brought a new level of cinematic communication. This innovative approach improved the clarity of dialogue delivery and made the narrative flow smoother, allowing seamless transitions between scenes.

Narrative Techniques

After 1907, there was a significant change in the way filmmakers told their stories. They focused on perfecting their storytelling skills to engage and fascinate their viewers. There were new ways to express creativity and themes in every movie story, from complex plots to character development.

Motion Pictures Patent Company (MPPC)

During the period of 1895–1905, inventors and entrepreneurs paved the way for the cinema business in the United States. By 1908, Edison realized that the growth of Nickelodeons using pirated films resulted in a large loss of revenue. Edison formed the MPPC with nine other producers to control the film production and distribution business. The three-part structure in the film industry emerged involving the producer, the distributor and the exhibitor of motion pictures, as it does today.

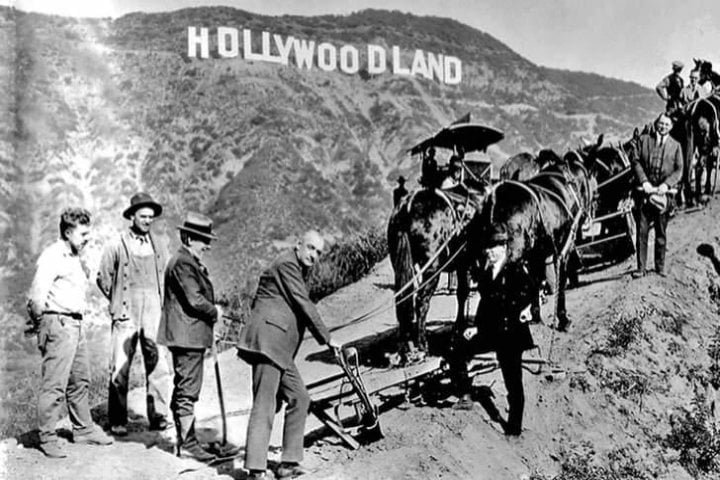

Independent producers challenged this monopoly and a patent war ensued. Independent producers decided to import their own films from Europe. During this Patent War, trusts hired gunman to seek out independent producers and try to put them out of business. Some independents sought better locations for all-year shooting and settled in a remote town in California called Hollywood.

One of the rebellious independent producers was Edwin.S.Porter, who left Edison in 1912 to start a new company called ‘Famous Players’ along with his friend Adolf Zukor. They produced films like The Count of Monte Cristo (1913) and The Prisoner of Zenda (1913), which gives cinema some prestige as an art form but contribute little towards narration and cinematic storytelling.

D.W. Griffith used his experience at ‘Biograph Studios’ to demonstrate that how stories can be told cinematically. He made some important observations, like, ‘Films could recreate the activities of the mind’ by focusing attention on one object or another (by means of a close-up), recall memories or project imaginings (by flashback, or flashforward), and interplay between events (by means of cross-cutting)”.

He introduced the concept of breaking down a scene into a series of cinematic units called shots. He used editing techniques like cross-cutting, camera angles, artificial lighting, realistic sets, flashbacks, split screens, soft focus, dissolves and fades, to manipulate time and space.

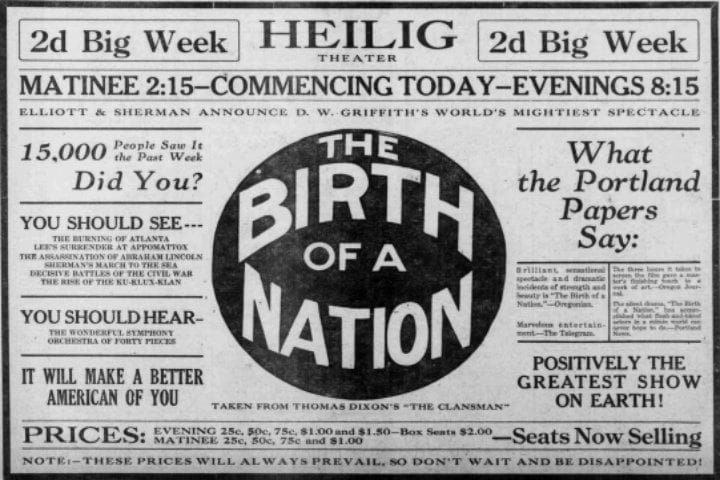

Beginning of the Hollywood Studio System

D.W. Griffith, also known as the ‘Father of the American Film,’ produced and directed over 400 one-reel and two-reel films for Biograph Studios, along with two epics, The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916), which became the ‘grammar and rhetoric’ for a feature-length film.

Between 1919 and 1929, the American film industry grew and prospered in Hollywood. The Golden Age of Hollywood begins with the end of the silent era in American cinema in the late 1920s. It was the era of creativity and exploration. Narrative feature-length films, along with movie theaters’ popularity, brought about Hollywood’s rise.

Hollywood’s Golden Age

The success of the first talkie (film with sound), The Jazz Singer (1927), gave a big boost to the Warner Bros. studio, which was a mid-sized studio at that time. The following years saw the general introduction of sound throughout the industry.

1927 and 1928 were considered as the beginning of Hollywood’s Golden Age and the final steps in the establishment of studio system control of the film business.

During the Golden Age, The studios created the films, had the writers, directors, producers and actors on their pay-roll, owned the film processing and laboratories, created the prints and distributed them through the theatres that they owned. In other words, the studios were vertically integrated.

By the 1930s, Hollywood was one of the most visible businesses in America, and most people were attending films at least once a week. By 1945, the studios owned either partially or outright 17% of the theatres in the country, accounting for 45% of the film-rental revenue.

Only eight companies comprised the major studios in the Hollywood studio system. Of these eight, Big Five were fully integrated, i.e. combining ownership of a production studio, distribution division, and theater chain: Fox (later to become 20th Century-Fox), Loew’s Incorporated (owner of America’s largest theater chain and parent company to MGM), Paramount Pictures, RKO and Warner Bros. The Little Three were Universal Studios, Columbia Pictures, and United Artists.

Better sound and film technology and strong narratives involving romantic characters attracted audiences to the Hollywood film industry.

Products of the Golden Age include a long list of movies that are today seen as classics: The Wizard of Oz, Gone with the Wind, Casablanca, It’s a Wonderful Life, It Happened One Night, King Kong, Citizen Kane, Some Like It Hot, Singin’ in the Rain, Roman Holiday, and many more.

Though the Golden Age is known for producing classics, it was criticized for standardizing how movies were produced. Due to the studio system, actors and directors thought of themselves as employees, not artists.

The Paramount Case

The Hollywood Antitrust Case of 1948 resulted in a landmark judgment by the United States Supreme Court that decided the fate of movie studios owning their own theatres and holding exclusivity rights on which theatres would show their films. It also changed how Hollywood movies were produced, distributed, and exhibited.

The Supreme Court ruled against these unfair distribution and exhibition practices (vertical integration) and ended the studio system, giving those “Big 5” studios control of the entire film market. This judgment is responsible for ending the old Hollywood studio system.

The Cinema section in the CUET UG 2024 Mass Media and Communication syllabus includes this topic.