Part 1: Historical Context of Media and Language Politics

The role of media in shaping linguistic identity and subsequently influencing the formation of states in India has its roots in the pre-independence era. To understand this complex interplay, we must examine the historical context of media and language politics in colonial India.

The Rise of Print Media and Vernacular Press

The introduction of the printing press in India by Portuguese missionaries in the 16th century marked the start of a new era in communication. However, indigenous print media flourished not until the late 18th and early 19th centuries. During this time, newspapers and periodicals in different Indian languages appeared alongside English publications.

Key developments include:

1780: The Bengal Gazette, the first English-language newspaper in India, was established by James Augustus Hicky.

1818: Samachar Darpan, the first Bengali newspaper, was published by the Serampore Mission Press.

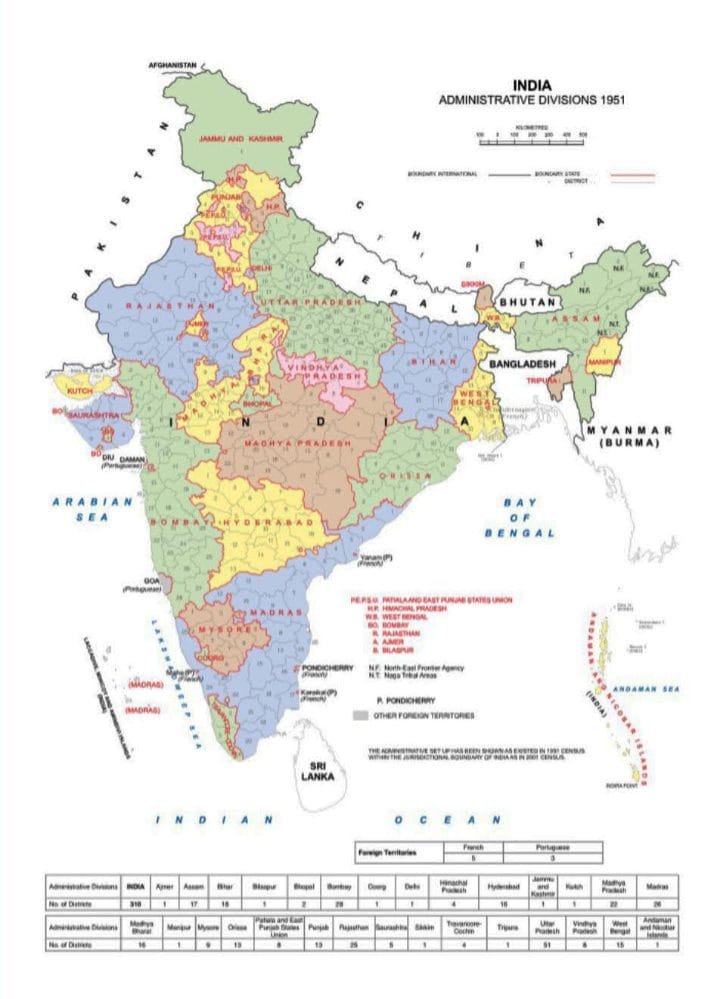

1822: Mumbai Samachar, India’s oldest continuously published newspaper, was founded in Gujarati.

These publications, particularly those in vernacular languages, encouraged linguistic identity and regional consciousness.

Language Standardization and Literary Movements

The 19th century witnessed significant efforts to standardize and modernize Indian languages. This process was closely tied to the growth of print media.

Bengali: The works of scholars like Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar helped standardize Bengali prose, which was then widely disseminated through newspapers and books.

Hindi: The Hindi-Urdu amalgamation in the late 19th century led to the development of Khari Boli Hindi as a distinct literary language, promoted through publications like “Hindi Pradip” (1877).

Tamil: The Pure Tamil Movement (Tanittamil Iyakkam) in the early 20th century sought to purge Tamil of Sanskrit influences, using magazines and newspapers as platforms for debate.

These linguistic movements, often championed through the press, laid the groundwork for later demands for linguistic states.

Colonial Policies and Press Regulations

British colonial policies significantly impacted the development of Indian-language media.

Vernacular Press Act (1878): This act sought to limit seditious content in Indian-language newspapers, but it unintentionally increased awareness of linguistic and regional identities. This act, though restrictive, recognised the increasing impact of the vernacular press on public opinion.

Indian Press Act of 1910: Lord Minto II, the Viceroy of India, implemented the Indian Press Act of 1910. Section 12(1) of the Act empowered the local governments to issue warrants against any newspaper or book that contained seditious matters, which were to be forfeited to his majesty.

Nationalism and Linguistic Identity

The Indian nationalist movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was closely linked to issues of language and identity.

Early Demands for Linguistic Provinces

The idea of reorganizing Indian provinces on linguistic lines began to gain traction in the early 20th century.

1913: Demand begins for a separate Andhra State from Telugu-speaking regions of Madras Presidency.

1920: Earlier in 1920, the members of the Indian National Congress had agreed on the linguistic reorganisation of the Indian states as one of the party’s political goals. The Provincial Committees of the party were set on this basis since 1920.

1927: The Congress declared that it was committed to “the redistribution of provinces on a linguistic basis” and reaffirmed its stance several times, including in the election manifesto of 1945-46.

1928: Motilal Nehru Committee Report recommends linguistic provinces, subject to administrative and financial considerations.

Early demands were widely discussed and spread through regional language newspapers and periodicals, paving the way for post-independence movements for linguistic states.

The pre-independence era saw the emergence of a robust vernacular press that played a crucial role in shaping linguistic identities and regional consciousness. This media landscape, interacting with colonial policies, nationalist movements, and early demands for linguistic provinces, laid the foundation for the complex process of state formation in independent India.

Part 2: The State Reorganization Act 1956

The State Reorganization Act of 1956 was a watershed moment in the history of independent India, fundamentally reshaping the country’s internal boundaries along linguistic lines. This act was the culmination of years of debate, agitation, and media discourse on the question of linguistic states.

Background to the Act

After gaining independence in 1947, India inherited the administrative divisions of British India, which were not based on language. Linguistic groups in India increased their demands for separate states, with the Telugu-speaking regions advocating for the formation of Andhra Pradesh.

Dhar Commission (1948): On 17 June 1948, Rajendra Prasad, the President of the Constituent Assembly, established the Linguistic Provinces Commission, known as the Dhar Commission, to assess the reorganization of states based on language. The committee comprised SK Dhar, a retired Judge of the Allahabad High Court; Jagat Narain Lal, a lawyer and member of the constituent assembly; and Panna Lall, a retired Indian Civil Service officer.

In its 10 December 1948 report, the Commission recommended that the formation of provinces on exclusively or even mainly linguistic considerations is not in the larger interests of the Indian nation. The commission recommended reorganization based on administrative convenience, not linguistic considerations.

JVP Committee (1949): The Congress established the JVP Committee in December 1948 during its Jaipur session to examine the Dhar Commission’s recommendations. The committee included Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, and Congress president Pattabhi Sitaramayya.

The Committee’s report dated 1 April 1949 indicated that it was not the right time to form new provinces, yet noted that there was strong public sentiment favouring states based on language.

The Catalyst: The Andhra Movement

A detailed report titled “When Tamils and Telugus tussled for Madras,” published in The Hindu, mentioned that a separate province carved out of the Madras Presidency to form Andhra gained momentum in the 1940s and 1950s.

The Telugus wanted Madras to be the capital of Andhra Pradesh, hence the slogan “Madras Manade” (Madras is ours). What followed were numerous meetings, demonstrations, and strikes in the city. Some of the leaders at the forefront of this movement were Tanguturi Prakasam (who later became the first Chief Minister of Andhra State), Bulusu Sambamurti, B. Gopala Reddy, Bhogaraju Pattabhi Sitaramayya, Neelam Sanjiva Reddy (the first Deputy Chief Minister of Andhra State who went on to become the President of India), and Tenneti Viswanatham.

A parallel slogan, ‘Madras Namade’, (Madras is ours), was launched by Tamil patriot and scholar Ma. Po. Sivagnanam (Ma. Po. Si.) through his Tamil Arasu Kazhagam. To retain Madras as the Tamil capital, Ma. Po. Si. organized rallies and protests with the Tamil slogan ‘Thalai Koduthenum Thalainagar Kaapom’ translated as ‘We will save the capital by parting with our heads’ and ‘Vengadathai Vidamattom’ (We will not give up Tirupati).

“In November 1949, the Congress Working Committee recommended Andhra State to be formed but without Madras city,” wrote historian A.R. Venkatachalapathy in the book Chennai Not Madras: Perspectives on the City.

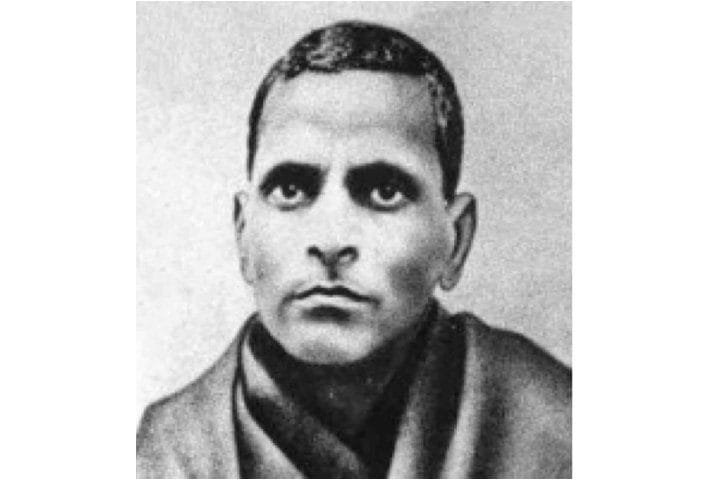

Potti Sreeramulu

Potti Sreeramulu, born March 16, 1901, was an Indian freedom fighter and revolutionary committed to establishing a separate Telugu-speaking state. In October 1952, Sreeramulu started a fast to request the separation of Telugu-speaking districts from the Madras Presidency.

The fast lasted 58 days and gained significant public attention, despite the disapproval of the Andhra Congress committee. Public unrest increased during the fast, with strikes and demonstrations spreading throughout the Andhra region.

Sreeramulu died on December 15, 1952, after fasting for nearly two months. His death led to public riots and violence in multiple regions of Andhra. Following Sreeramulu’s death, the situation escalated rapidly. On December 19, 1952, Prime Minister Nehru declared the government’s plan to create a separate Andhra State.

Andhra Pradesh was formed from Madras State on October 1, 1953, with Kurnool as its capital. Madras retained its capital, while Tirupati became part of Andhra, establishing a precedent for linguistic reorganisation.

Sreeramulu’s dedication and sacrifice earned him the title “Amarajeevi” (Immortal Being) in Andhra.

Role of Telugu Press

The Telugu newspapers like “Andhra Patrika” and “Andhra Prabha,” played a crucial role in mobilizing public opinion and pressuring the government. The press has also played a key role in shaping public discourse and promoting linguistic and cultural identity in India. Telugu newspapers have:

- Disseminated information about the movement for a separate Telugu-speaking state.

- Provided a platform for local leaders and intellectuals to express their views on linguistic reorganization.

- Reported on key events, such as Potti Sreeramulu’s fast and subsequent death, which galvanized public opinion.

- It helped create a sense of shared linguistic and cultural identity among Telugu speakers.

The States Reorganization Commission (SRC)

The formation of states in India based on language was a complex and important process after independence. The States Reorganization Commission (SRC) was established in 1953 to address the increasing demands for linguistic states that had developed since before independence.

The SRC, made up of Justice Fazl Ali, K. M. Panikkar, and H. N. Kunzru, was assigned to assess the possibility of reorganizing Indian states based on language. This commission’s work was instrumental in shaping the future administrative map of India.

The SRC used a comprehensive methodology. They toured the country, received memoranda from various groups, and studied historical, cultural, and economic factors along with linguistic considerations. This approach ensured the commission’s recommendations were informed and considered multiple perspectives.

Media coverage of the SRC’s work by national and regional outlets sparked public debates on state boundaries. This coverage contributed to the development of an informed citizenry and promoted a democratic dialogue on the topic. The regional press played a crucial role in clarifying the commission’s recommendations to local populations in their native languages.

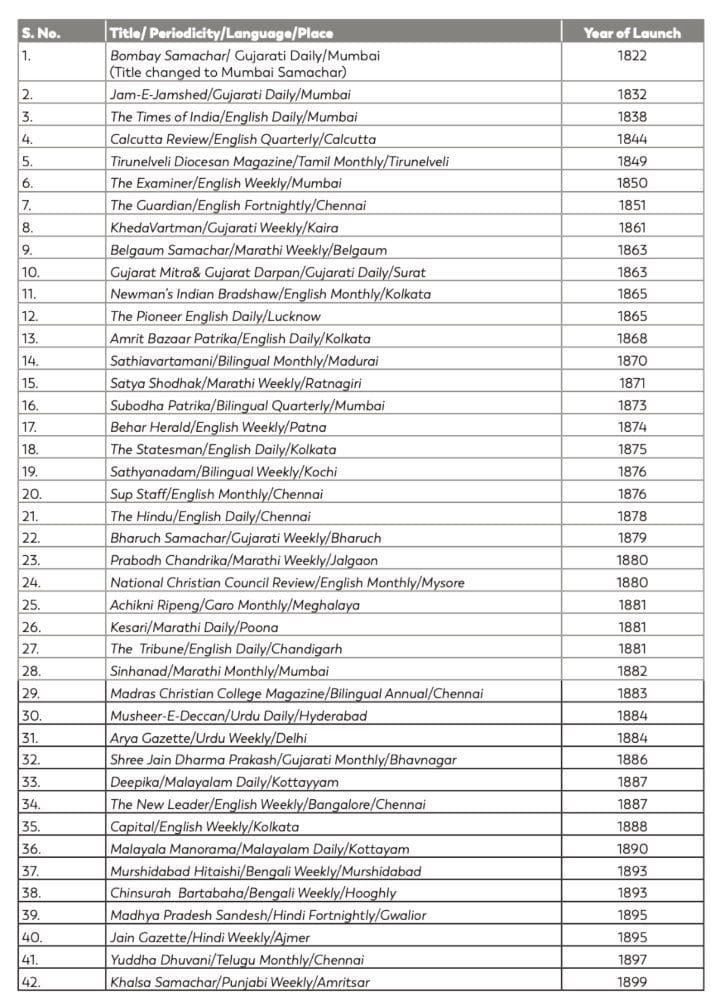

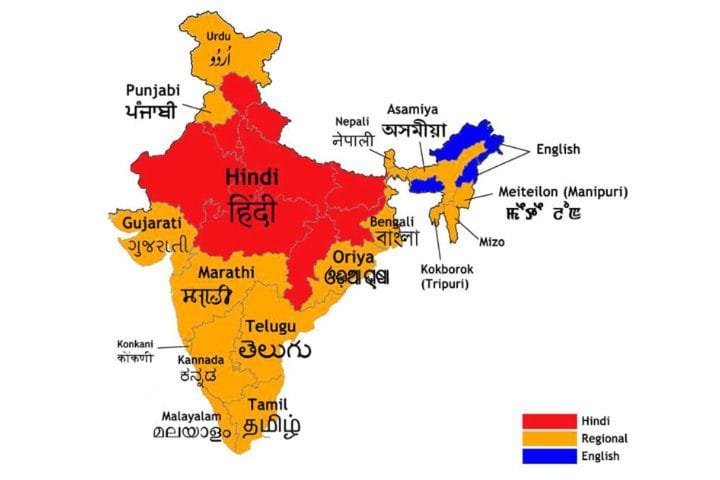

The formation of states in India on a linguistic basis involved historical, cultural, and political factors, with the States Reorganization Commission being central to the process. The States Reorganisation Act of 1956 resulted in the formation of 14 states and 6 union territories, primarily based on linguistic divisions.

Key Provisions of the State Reorganization Act, 1956

Reorganization: The act reorganized the boundaries of India’s states and territories, reducing their number from 27 to 14 states and 6 union territories.

Linguistic Basis: While language was a primary consideration, other factors like geography, economy, and culture were also taken into account.

Major Changes:

- Creation of linguistic states like Kerala, Karnataka, and Madhya Pradesh

- Reorganization of existing states like Bombay (later split into Maharashtra and Gujarat in 1960)

- Merger of several princely states into larger units

Controversies and Debates

- The act resulted in multiple border disputes among newly formed states, which received significant media coverage and debate.

- Concerns about the status of linguistic minorities in the new states were prominently featured in media discussions.

- Media coverage frequently debated the economic feasibility of smaller linguistic states.

Long-term Impact

- The reorganization changed India’s political landscape, leading to the emergence of regional political parties and movements.

- Various linguistic groups saw a cultural revival after establishing their states, often showcased and supported by regional media.

- The reorganization created new administrative challenges that attracted media attention and public discussion.

The State Reorganization Act of 1956 significantly changed India’s internal geography after independence. The media, especially the vernacular press, was essential in expressing regional aspirations, shaping public opinion, and impacting the reorganization process. This act set a precedent for future state formations and continues to influence India’s political and cultural landscape to this day.

Part 3: Prominent Press in States Formed on a Linguistic Basis

The creation of linguistic states in India after the State Reorganization Act of 1956 significantly affected the media landscape, especially the vernacular press. The major press in key states formed on a linguistic basis, influencing regional identities and political discourse.

Andhra Pradesh (Telugu)

Andhra Pradesh, established in 1956, led the linguistic state movement. The Telugu press played a crucial role in its formation and subsequent development.

Andhra Patrika: Founded in 1908, it was instrumental in the Andhra movement. After the reorganization, it remained an important influence in defining Telugu cultural identity.

Andhra Prabha: Established in 1938, it gained prominence during the struggle for Andhra State and remained influential after its formation.

Eenadu: Launched in 1974, it revolutionized Telugu journalism with its focus on local news and innovative management practices.

These newspapers not only reported news but also actively participated in cultural and literary movements, promoting Telugu language and literature.

Kerala (Malayalam)

Kerala, established in 1956, has a rich tradition of Malayalam journalism that existed before it became a linguistic state.

Malayala Manorama: Founded in 1888, it played a significant role in the socio-political life of Kerala. Post-1956, it continued to be a major influence in shaping public opinion.

Mathrubhumi: Established in 1923 as a nationalist newspaper, it was closely associated with the independence movement and later became a key player in Kerala’s media landscape.

Kerala Kaumudi: Started in 1911, it was known for its progressive stance and played a crucial role in social reform movements.

Malayalam newspapers served as news outlets and platforms for literary and cultural discourse, significantly contributing to Kerala’s high literacy rates and political awareness.

Maharashtra (Marathi)

Maharashtra was formed in 1960, separating from the bilingual Bombay State. The Marathi press had a long history of political activism.

Kesari: Founded by Lokmanya Tilak in 1881, it continued to be influential in post-independence Maharashtra, championing Marathi causes.

Maharashtra Times: Launched in 1962, it quickly became a leading Marathi daily, known for its balanced reporting and cultural coverage.

Loksatta: Started in 1948, it gained prominence for its progressive editorial stance and focus on social issues.

These newspapers played a crucial role in articulating the aspirations of the Marathi-speaking population and shaping Maharashtra’s distinct political culture.

Tamil Nadu (Tamil)

Tamil Nadu (initially Madras State) was reorganized in 1956 and renamed in 1969. The Tamil press has a long and vibrant history closely tied to the Dravidian movement.

Dina Thanthi: Founded in 1942, it pioneered a colloquial style of writing that made news accessible to the masses.

Dinamani: Established in 1934, it was known for its nationalist leanings and later became a platform for promoting Tamil language and culture.

Murasoli: Started in 1942 as a Tamil weekly, it became the official organ of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) party and played a significant role in propagating Dravidian ideology.

These newspapers were instrumental in promoting Tamil identity and played a crucial role in the anti-Hindi agitations of the 1960s.

West Bengal (Bengali)

Although West Bengal was not created by the 1956 act (it was formed in 1947), it’s worth mentioning due to the significant role of its Bengali press.

Anandabazar Patrika: Founded in 1922, it emerged as the most widely read Bengali newspaper, known for its comprehensive coverage and literary supplements.

Jugantar: Established in 1937, it was known for its nationalist stance and continued to be influential in post-independence West Bengal.

Dainik Basumati: Started in 1914, it played a significant role in promoting Bengali literature and culture.

These newspapers were crucial in shaping Bengali cultural identity and political discourse in West Bengal.

Karnataka (Kannada)

Karnataka was formed in 1956, unifying Kannada-speaking regions.

Prajavani: Launched in 1948, it quickly became one of the most widely read Kannada newspapers, known for its balanced reporting.

Samyukta Karnataka: Founded in 1929, it played a significant role in the unification of Karnataka and continued to be influential post-1956.

Udayavani: Started in 1970, it gained popularity for its focus on local news and cultural coverage.

These newspapers were instrumental in promoting Kannada language and culture and in shaping the political discourse in the newly formed state.

Part 4: Role of the Press in the Formation of States in India

The press played a key role in shaping states in India, particularly in linguistic reorganization. Let’s discuss the role of the press in this process, highlighting its influence on public opinion, political decision-making, and the shaping of regional identities.

Articulation of Regional Aspirations

Platform for Demands: The press, especially vernacular newspapers, served as a primary platform for articulating demands for separate statehood based on linguistic lines.

Amplification of Local Voices: Regional newspapers amplified the voices of local leaders and activists, bringing their demands to a wider audience and to the attention of national leadership.

Example: The Telugu press, including publications like “Andhra Patrika” and “Andhra Prabha,” was instrumental in voicing the demand for a separate Andhra state, which ultimately led to the creation of Andhra Pradesh.

Shaping Public Opinion

Mass Mobilization: Newspapers played a crucial role in mobilizing public opinion in favor of linguistic states. They often used emotive language and cultural symbolism to appeal to regional sentiments.

Creating Awareness: The press educated the public about the potential benefits and challenges of linguistic reorganization, fostering informed debates.

Example: In Maharashtra, newspapers like “Kesari” played a significant role in building public support for the Samyukta Maharashtra movement, which eventually led to the creation of Maharashtra as a separate state.

Pressure on Political Leadership

Advocacy Journalism: Many newspapers adopted an advocacy role, directly pressuring political leaders to act on the demands for linguistic states.

Critical Reporting: The press critically analyzed government policies and decisions related to state reorganization, often influencing the direction of political discourse.

Example: The Tamil press, including “Dina Thanthi” and “Dinamani,” was instrumental in building pressure for the renaming of Madras State to Tamil Nadu in 1969.

Preservation and Promotion of Linguistic Identity

Language Standardization: Newspapers played a crucial role in standardizing regional languages, often resolving dialectical differences and promoting a unified linguistic identity.

Cultural Promotion: Through literary supplements and cultural coverage, the press reinforced the distinct cultural identities of linguistic groups.

Example: Bengali newspapers like “Anandabazar Patrika” not only reported news but also played a significant role in promoting Bengali literature and culture, reinforcing the linguistic and cultural identity of West Bengal.

Inter-regional Debates and Negotiations

Forum for Debate: The press provided a platform for debating the merits and demerits of proposed state boundaries, often featuring opinions from various stakeholders.

Conflict Resolution: In some cases, the press played a mediating role in resolving inter-regional conflicts arising from competing claims over territories.

Example: During the formation of Punjab and Haryana, newspapers in both regions facilitated debates on the division of resources and territories, influencing the final demarcation of boundaries.

Influencing National Policy

Agenda Setting: By consistently highlighting regional demands, the press played a role in setting the national agenda, forcing the central government to address the issue of linguistic reorganization.

Policy Criticism: The press critically analyzed national policies on state reorganization, often leading to policy revisions.

Example: The extensive coverage of the fast unto death by Potti Sriramulu in the Telugu and national press in 1952 forced the central government to expedite the process of linguistic reorganization.

Balancing Regional and National Interests

Promoting Integration: While advocating for linguistic states, many newspapers also emphasized the importance of national unity, helping to balance regional aspirations with national interests.

Addressing Minority Concerns: The press often highlighted the concerns of linguistic minorities within proposed states, contributing to more nuanced policy decisions.

Post-Formation Role

State Building: After the formation of new states, the press played a crucial role in state-building processes, fostering a sense of belonging among citizens and scrutinizing governance in the new administrative units.

Continued Advocacy: In some cases, the press continued to advocate for further reorganization or for addressing unresolved issues stemming from the initial reorganization.

Example: Even after the formation of Andhra Pradesh, the Telugu press played a significant role in the movement for a separate Telangana state, which was eventually formed in 2014.

The press was essential in shaping the formation of states in India. It provided a means to express demands, influence public opinion, pressure political leaders, and maintain linguistic and cultural identities. The press reflected the aspirations of linguistic communities and participated in state formation, influencing policy decisions and reshaping India’s political map. Its role went beyond reporting and became essential to the socio-political process that resulted in the linguistic reorganization of states in India.