CUET UG Cinema

Indian Parallel Cinema: Introduction

“Indian Parallel Cinema,” also known as “Indian New Wave Cinema” and “Alternative Cinema,” is a film movement that gained prominence in the 1950s in the state of West Bengal, India. At that time, commercial films were more popular and known for being melodramatic, with excessive glamour and many songs and dances far from reality.

On the other hand, Parallel Cinema revolutionized Indian cinema by emphasizing realistic storytelling, which is intellectually stimulating and engaging, with minimal use of music and glamour.

However, parallel cinema never really had mass appeal. It was meant for a niche; only a certain section of the audience would be interested in this kind of cinema. The topics explored in these films were issue-based and derived from the nation’s sociopolitical and socioeconomic milieu.

Indian parallel cinema explored issues like casteism in society and the position of women and their objectification, as well as subjugation by males or by the patriarchal structure of society.

Filmmakers of Indian parallel cinema were also exploring themes of partition and the feeling of rootlessness associated with it. These films also explored themes like communal disharmony and told tales of the peasant class of society.

Unlike popular mainstream cinema, these films were realistic in approach, and their content was purposeful and meaningful.

Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Shyam Benegal, and others are among the most prominent filmmakers associated with parallel cinema.

Cinema as an Art Movement

The Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) was established in 1942 as an organization that aimed to integrate and popularize the cultural movement alongside the struggle for freedom. It brought together cultural troupes, cultural activists, and theater groups, shaping the movement throughout the 1940s and 1950s.

Several realistic IPTA plays, such as Bijon Bhattacharya’s Nabanna (1944), based on the tragedy of the Bengal famine of 1943, prepared the ground for realism in Indian cinema.

A few noteworthy cinematic products of this movement were Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s Dharti Ke Lal (1946), Mehboob’s Mother India (1957), and Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (1957).

Golden Age of Indian Cinema

The ‘Golden Age’ of Indian cinema spans from the late 1940s to the 1960s. Some of the most critically acclaimed Indian films emerged during this period.

Films like Raj Kapoor’s Awaara (1951) and Shree 420 (1955), Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (1957) and Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959), Mehboob Khan’s Mother India (1957), K. Asif’s Mughal-e-Azam (1960), V. Shantaram’s Do Aankhen Barah Haath (1957), and Bimal Roy’s Madhumati (1958) are the epic films of Hindi cinema.

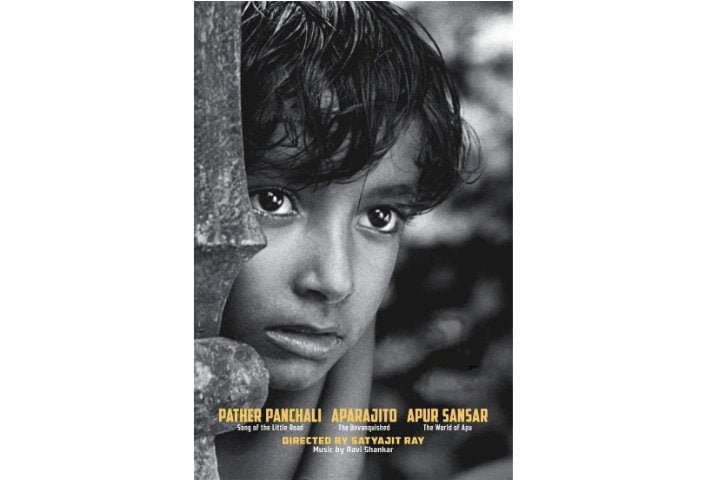

A brand-new parallel cinema movement emerged in the same era, with Bengali cinema as its main leader. Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar (1946), Ritwik Ghatak’s Nagarik (1952), Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zameen (1953), and The Apu Trilogy (1955–1959) by Satyajit Ray, which includes Pather Panchali (1954), Aparajito (1956), and Apur Sansar (1959).

The Apu Trilogy won major prizes at all the major international film festivals and led to the firmly established ‘Parallel Cinema’ movement in Indian cinema.

Major film festivals worldwide frequently accepted and awarded several prizes to social realist films of that era. Satyajit Ray won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for Aparajito (1956), the Golden Bear, and two Silver Bears for Best Director at the Berlin International Film Festival.

Other renowned Indian independent filmmakers, including Mrinal Sen, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Mani Kaul, and Buddhadeb Dasgupta, followed Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak in directing numerous additional critically acclaimed “art films.”

Catalysts of the Indian Parallel Cinema Movement

Since independence, people have recognized the importance of films as tools for mass communication. People felt the need to expand the cinema’s audience and create films that reflected societal issues. The “Film Inquiry Committee” was set up in 1949. In 1951, the committee submitted a report with a couple of recommendations. These were

- Financing body for films for easier funding

- Training institute for film technicians

- Film Festival to promote Indian Cinema

- National Awards for Filmmakers

- Establishment of Film Censor Board for Film Certification

The first Indian International Film Festival was organized in 1952. Another important recommendation was to establish a funding body for films. This would provide funding for films that were not considered commercially viable, allowing filmmakers to tell different stories.

After India gained independence in 1947, the various regional censor bodies were consolidated into the Bombay Board of Film Censors, later renamed the Central Board of Film Censors following the Cinematograph Act of 1952. Subsequently, in 1983, after the revision of cinematography rules, it was restructured and became the Central Board of Film Certification.

In 1960, a ‘Film Finance Corporation’ [which became NFDC (National Film Development Corporation) in 1975] under the Ministry of Finance was established, leading to offbeat cinema production.

In 1961, the FTII (Film and Television Institute of India), a training institute for film technicians and personnel, was set up in Pune.

This led to a shift in the form and content of films, which began in the late 1960s and persisted throughout the 1970s and 1980s. This change is reflected in the form of parallel cinema.

Indian Parallel Cinema Directors

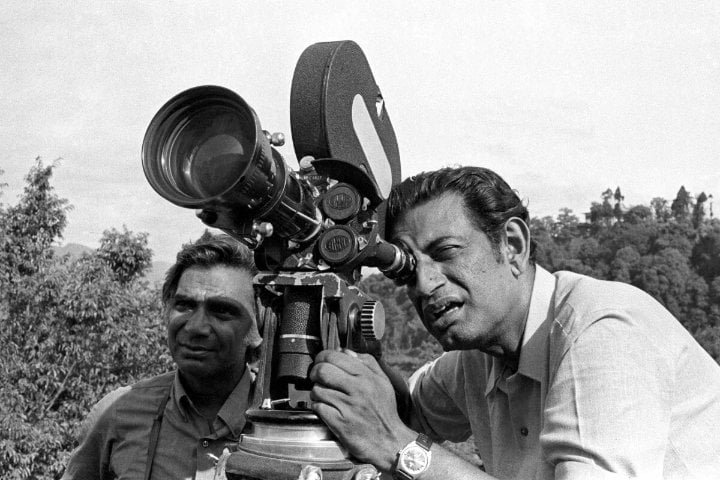

Satyajit Ray

Satyajit Ray is one of the most internationally acclaimed Indian filmmakers ever. The Italian neorealist cinema and French New Wave filmmaker Jean Renoir influenced Satyajit Ray.

Satyajit Ray met Jean Renoir in 1949 while scouting locations in Kolkata for his film, The River. Ray had the opportunity to interact with and assist Jean Renoir during his extensive shoot in Bengal.

Ray developed a sense of what cinema should be or what it should do for society. He proceeded to create his debut film, Pather Panchali (1955), garnering international acclaim and serving as a component of the Apu Trilogy. Following Pather Panchali were Aparajito (1956) and Apur Sansar (1959). Italian Neorealism inspired the trilogy, the coming-of-age tale of a young boy named Apu.

In making Pather Panchali, Ray followed the Italian neorealist approach by casting non-professional actors and filming on location to capture a sense of reality. Due to budget constraints, the film had to be completed in multiple stages, with Ray constantly seeking funding from different sources.

Despite these challenges, Pather Panchali received widespread acclaim, both nationally and internationally, for its significant contribution to the world of cinema.

Satyajit Ray received numerous national and international honors, including the Bharat Ratna, the highest civilian honor in India. He was also awarded the Dadasaheb Phalke Award and an Oscar for Lifetime Achievement in filmmaking.

Ray’s cinema was criticized for portraying India negatively and glorifying the poor and downtrodden, yet it set the standards for an alternative to mainstream Bombay cinema.

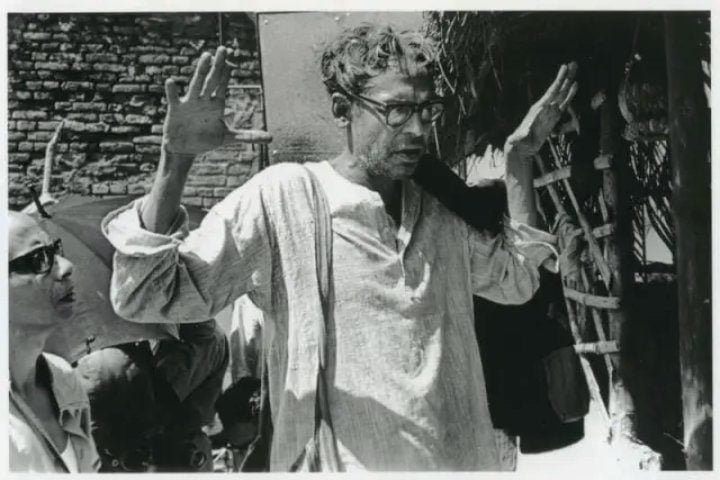

Ritwik Ghatak

Ritwik Ghatak is another filmmaker associated with the Indian New Wave. He was involved with IPTA before transitioning to filmmaking. Later, he also began teaching filmmaking at FTII.

Ghatak made films influenced by the partition, as he experienced the hardships of migration himself. Therefore, the main themes depicted in his films revolved around displacement, disillusionment, and feeling like a refugee in one’s own country.

He has directed films such as “Meghe Dhaka Tara” (1960) and “Subarnarekha” (1965).

Mrinal Sen

Mrinal Sen was associated with IPTA, and his films focused on socialist themes. Unlike mainstream cinema, he intentionally avoided happy endings.

Mrinal Sen’s influential film “Bhuvan Shome” was released in 1969 and is considered one of his most important works. This film is credited with bringing the parallel cinema movement to Hindi cinema, expanding it from its roots in Bengali cinema. Some of his other notable films include “Mrigayaa” (1976) and “Ek Din Achanak” (1989).

Shyam Benegal

Shyam Benegal is a significant filmmaker who has contributed substantially to Hindi cinema. He is credited with bringing parallel cinema into the Hindi film industry following Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome.

He made films like Ankur (1973), Nishant (1975), Bhumika (1977), Manthan (1976), Junoon (1978), and Mandi (1983). Benegal’s films became known as middle cinema because they addressed the issues and concerns of the middle class. Another interpretation of this term is that Benegal’s films navigated a middle ground between mainstream and parallel cinema.

On one hand, his films were not high-budget productions with star-studded casts, but they did include some mainstream cinema elements, such as catchy songs. Benegal did not like the term ‘middle cinema’ and preferred to call the cinema he made ‘new cinema’ or ‘alternative cinema.’

Critics and audiences enthusiastically embraced his films, garnering both national and international recognition for the subjects they tackled. Benegal was honored with the Padma Shri, Padma Bhushan, and Dadasaheb Phalke Awards for his significant contributions to cinema.

Kumar Shahani

Kumar Shahani was an alumnus of FTII, and his films were very experimental in nature. He made the film Maya Darpan in 1972. Although the public did not receive it well, it remains a significant film in the history of Hindi cinema.

He also made Khayal Gatha, an experimental film that uses a very abstract format to tell the history of Khayal music. Kasba was another film he made in 1991.

Mani Kaul

Mani Kaul is yet another critical director associated with parallel cinema. He, too, was a student of Ritwik Ghatak. An alumnus of FTII, he later went on to teach the process of filmmaking at various institutes in India and abroad. His works were very experimental in nature; he broke conventional narrative styles and used very little dialogue in his films.

One of the first films he made was Uski Roti, which came out in 1969; another film was Duvidha, which came out in 1973. Asadh Ka Ek Din (1971) and Satah Se Utha Aadmi (1980) are his other films. The film titles demonstrate how their storylines address common people and everyday issues.

Govind Nihalani

Another important director of this era was Govind Nihalani. He started his career in 1962 and made his first feature film, Aakrosh (1980). He is known for making intense films with deep political undertones and dark and frighteningly real depictions of human angst. Ardha Satya (1983) and Tamas (1988) are his landmark parallel films.

Ardha Satya established him and Om Puri as the pillars of Indian parallel cinema. Govind Nihalani’s Tamas, a TV series based on Bhishma Sahani’s novel of the same name, is one of the most profound portrayals of partition on celluloid. Hazar Chaurasi Ki Ma, another movie he directed, was based on a book by Mahasweta Devi.

Ketan Mehta

Ketan Mehta is a known Indian director who has directed several movies, TV serials, and documentaries. He started his career in 1975 and has delivered several super hits since then. Like his other contemporary Indian parallel cinema directors, he was also an alumnus of the Film and Television Institute of India in Pune.

In 1980, Ketan Mehta directed his first film, Bhavani Bhavai. Some of his other popular works include Holi (1984), Mirch Masala (1987), Hero Hiralal (1989), Sardar (1993), Maya Memsaab (1993), Aar Ya Paar (1997), Manju: The Mountain Man (2015), and Mangal Pandey: The Rising (2005).

Ketan Mehta’s directorial Mirch Masala, holds an important place in the history of Indian cinema. Forbes has called Smita Patil’s performance in Mirch Masala one of the 25 best performances in Indian cinema ever.

Ketan Mehta received the National Film Award for Bhavani Bhavai and Sardar, a Filmfare Award, and the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French government.

M S Sathyu

M. S. Sathyu (Mysore Srinivasa Sathyu) is a celebrated filmmaker, theater director, stage designer, and art director known for his significant contribution to Indian parallel cinema. His thoughtfully crafted films are poignant representations of the societal climate of their time and an expression of his personal political convictions. He was also a known patron of IPTA.

His work includes nine plays, eight feature films, three telefilms, and four teleserials. He is best known for his directorial debut, Garm Hava (1973), considered one of the landmark films of Hindi cinema, in which a Muslim businessman and his family struggle for their rights in post-partition India.

His prominent directorials include Chitegoo Chinte (1978) and Bara (1982), an adaptation of U. R. Ananthamurthy’s short story, which won the Best Film and Best Director awards at the Karnataka State Film Awards and the Filmfare awards. He was also a recipient of the Padma Shri in 1975.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Hrishikesh Mukherjee is considered one of the greatest Indian filmmakers. He directed 42 films over four decades and is a pioneer of India’s ‘middle cinema.’ His movies reflected changing middle-class values and blended mainstream populism and art cinema’s realism.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s cinematic universe was rooted in the authenticity of life. With films like Ashirwad (68), Guddi (1971), Anand (1971), Bawarchi (1972), and Khubsoorat (1980), he told specific yet universal stories that were full of grace and humor.

In the worlds his films created, friends and family played long-running practical jokes on each other. Things usually worked out in the end, and there was no villain.

He was honored with the Dada Saheb Phalke Award in 1999 and the Padma Vibhushan in 2001. He also won eight Filmfare Awards.

Basu Chatterjee

Basu Chatterjee was a bridge between two different types of Indian cinema: parallel cinema and mainstream commercial cinema. He began with parallel cinema and continued making those kinds of films, but his work was not hard to understand. His movies appealed to regular people, which was his biggest contribution to cinema.

His directorial debut, Sara Akash (1969), along with Mani Kaul’s Uski Roti (1969) and Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969), is considered the dawn of Indian parallel cinema.

In his films, he portrayed the delightful intricacies of everyday life through characters who carried the personality of the next-door boy or girl, in movies such as Piya ka Ghar (1971), Rajnigandha (1974), Chhoti Si Baat (1976), Chitchor (1976), Baton Baton Mein (1979), and Do Ladke Dono Kadke (1979).

Basu Chatterjee and Hrishikesh Mukherjee portrayed a gentler side of Hindi cinema, where there were no villains, just the challenges of life.

The directors mentioned have great significance in the parallel cinema movement. An interesting aspect of these films is that, as the parallel cinema movement progressed, it incorporated mainstream cinema conventions to appeal to a wider audience. This made parallel cinema more accessible, not just limited to a niche audience. Despite this, the themes and storytelling style remained true to the essence of parallel cinema.

The CUET UG Mass Communication syllabus contains this topic under the Cinema section.