- Concept of Socialization

- Media and Social Change

- Social Movements in India

- First War of Independence 1857

- Swadeshi Movement 1905

- Non-Cooperation Movement 1920

- Civil Disobedience Movement 1930

- Quit India Movement 1942

- Land Reform Movement in India

- Chipko Movement 1973

- Dalit Panther Movement 1972

- Mandal Commission Report and Caste-Based Reservation in India 1990

- Narmada Bachao Andolan 1985

- Right to Information Act (RTI) 2005

- India Against Corruption Movement (2011) and Lokpal Act (2013)

- India’s Awakening: The Nirbhaya Movement’s (2012) Impact

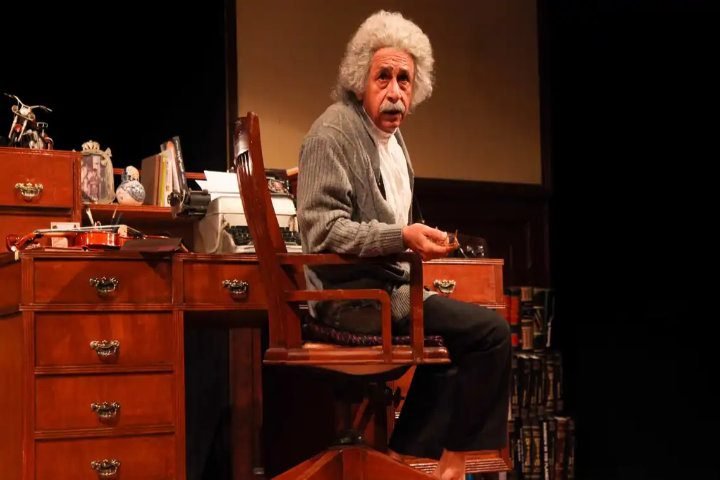

Mandal Commission Report

During the period of 1980–2000, India experienced significant socio-political and economic shifts. The 1980s marked a turning point with the rise of regional parties challenging the dominance of the Congress Party. Economic stagnation and political instability characterized much of this decade.

In This Article

However, in 1991, under Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao, India embraced economic liberalization, opening up its markets to globalization, which led to rapid economic growth in the following years. Politically, coalition governments became the norm, reflecting the diversification of India’s political landscape.

This era also witnessed significant technological advancements and the emergence of a new middle class, contributing to the transformation of India’s social fabric. Overall, India’s socio-political-economic climate from 1980 to 2000 was one of transition, with social movements, political realignments, and economic reforms all contributing to the country’s trajectory into the twenty-first century.

The period also saw unprecedented social upheavals, notably with the implementation of the Mandal Commission Report in 1990, which aimed to provide reservations for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in government jobs and educational institutions.

This move triggered widespread debate and protests, reflecting the tensions between caste-based politics and social justice.

Reservation for Social Upliftment

Before the Mandal Commission, India had experienced numerous endeavors aimed at implementing reservation policies. In 1950, the Constitution of India was enacted, which included provisions for reservations for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

The demand for comparable assistance to OBCs has also started since then. Although several southern Indian states had implemented reservation policies at the state level, a comprehensive national policy was absent in this regard.

The Kaka Kalekar Commission of 1953 was the first commission for backward classes. Despite producing a report listing nearly 2,399 communities as “backward,” the Commission had no substantial impact.

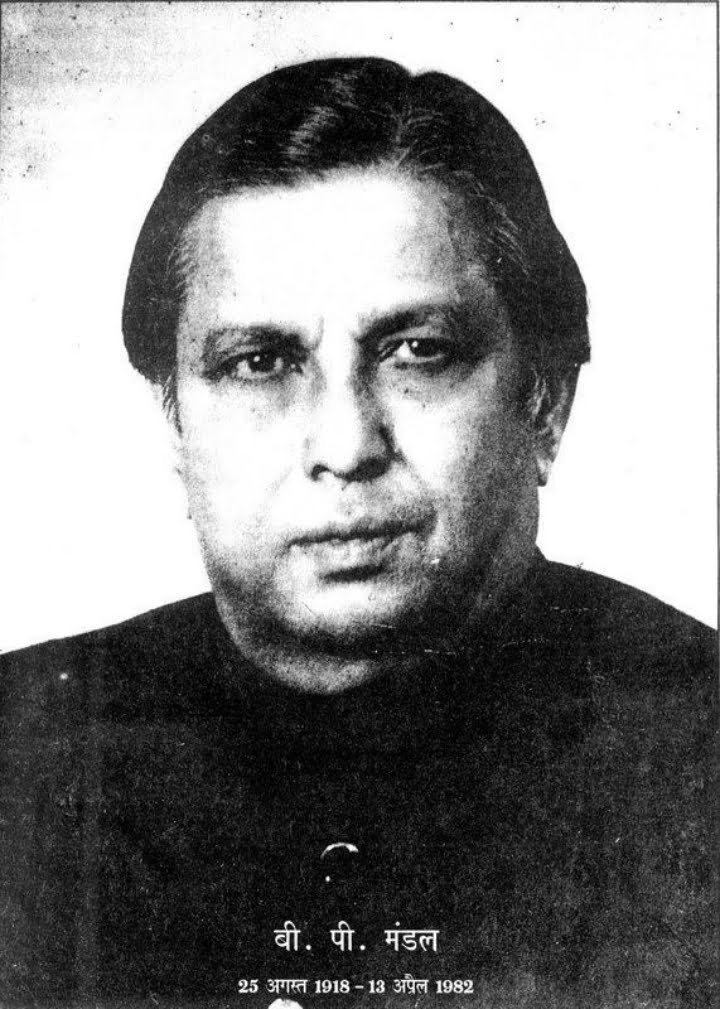

The Genesis of Mandal Commission

The Mandal Commission, officially known as the Socially and Educationally Backward Classes Commission, was constituted in India on January 1, 1979, to identify the socially and educationally backward classes of citizens and recommend measures for their advancement.

Its recommendations, particularly regarding reservations for Other Backward Classes (OBCs), have been the subject of intense debate and controversy ever since.

Objectives of the Mandal Commission

- The Commission was primarily responsible for addressing the challenges the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) encountered.

- It had to establish what criteria would define India’s “socially and educationally backward classes.”

- They had to suggest ways to help these classes move up and also look at reservations for jobs in the state and central governments.

Mandal Commission findings

- relying heavily on manual labor

- having family assets that are significantly below the state average

- being considered backward by other castes or classes

Recommendations made by the Mandal Commission

- 1979: The establishment of the Mandal Commission under the chairmanship of B.P. Mandal by Prime Minister Morarji Desai of the Janata Party.

- 1980–1990: The Mandal Commission conducts extensive surveys and research to identify socially and educationally backward classes.

- December 31, 1980: The Mandal Commission submits its report recommending 27% reservation for OBCs in government jobs and educational institutions.

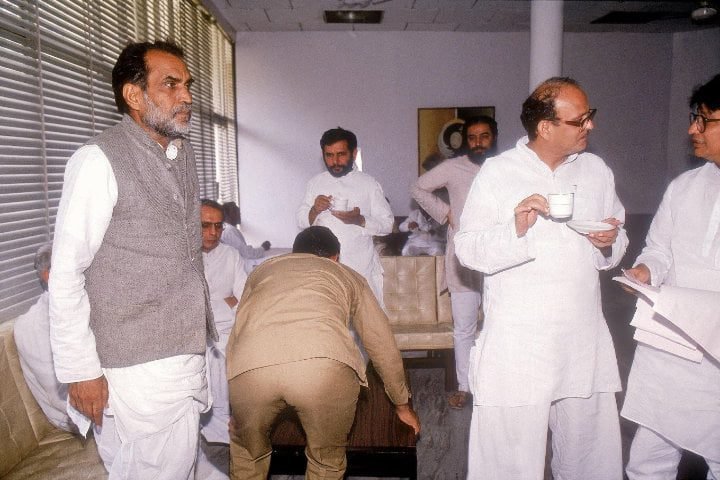

- August 7, 1990: Prime Minister V. P. Singh of the National Front coalition announced the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations through the Mandal Commission Reservation Act.

- September 1990: The recommendations trigger widespread protests and debates across the country. Critics argued that the reservation policies could lead to reverse discrimination and lower merit-based selection.

- November 16, 1992: The Supreme Court upheld the Commission’s quota for OBC, and the recommendations were gradually enforced.

- September 1993: Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao announced the widespread implementation of the recommendations

- Subsequent Years: Various legal challenges and amendments to reservation policies are made, leading to ongoing debates and controversies.

- October 2, 2023: The state government of Bihar released a caste survey, claiming that the extremely backward classes (EBCs) and other backward classes (OBCs) made up nearly 63% of the state’s population.

- Mandal 2.0: The demand for a nationwide caste census by the opposition parties led by Congress in the runup to the 2024 general elections in India.

The Impact of Mandal Commission on the Socio-Political Landscape of India

The recommendations had a profound impact on India’s socio-political landscape:

Empowerment of OBCs

- Implementing caste-based reservations allowed OBCs to access education and employment in government institutions.

- This led to a significant increase in the representation of OBCs in various sectors, including bureaucracy, politics, and academia.

- OBC communities, which had historically faced discrimination and marginalization, began to assert their rights and demand equal opportunities for socio-economic advancement.

Social Justice

- Advocates of reservation argue that it serves as a tool for addressing historical injustices and inequalities perpetuated by the caste system.

- By providing quotas in education and employment, reservation policies aim to create a level playing field and uplift those who have been historically disadvantaged.

Political Realignment

- Implementing the Mandal Commission report led to the emergence of caste-based politics and the rise of regional parties representing OBC interests.

- Regional parties, especially in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, such as the Rashtriya Janta Dal, Janta Dal (United), Samajwadi Party, and Bahujan Samaj Party, have championed the cause of OBC reservation, while national parties like the Bharatiya Janata Party and Congress have adopted varying stances.

- Caste became a significant factor in electoral politics, with parties forming alliances and coalitions based on caste identities to mobilize support. Considering the large number of OBCs, no political party can dare take a stand against it.

Backlash and Opposition

- Critics of reservation argue that caste-based quotas perpetuate caste divisions and undermine the principles of meritocracy.

- There is concern that reservation policies may lead to inefficiencies and compromises in governance, as appointments and admissions are based on caste rather than merit.

- Some communities, particularly those not covered by reservation quotas, feel marginalized and disenfranchised, leading to social tensions and conflicts.

Legal Challenges

- Reservation policies have been subject to numerous legal challenges, with the judiciary playing a crucial role in interpreting and upholding the constitutionality of reservation laws.

- The Supreme Court of India has delivered several landmark judgments regarding reservation policies, balancing the need for social justice with constitutional principles of equality.

The CUET UG 2024 Mass Media and Communication syllabus contains this topic under the Communication section.