CUET UG Social Movements

Introduction to the Quit India Movement

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Movement, was a critical phase in the Indian struggle for independence from British rule. Initiated in August 1942 under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, this movement marked a decisive turn towards India’s ultimate liberation in 1947.

The call for “Quit India” resonated deeply with the Indian populace, urging an end to British colonization through a strategy of non-violent resistance, or satyagraha.

Historical Context and Genesis of the Movement

Early Resistance and the Build-Up

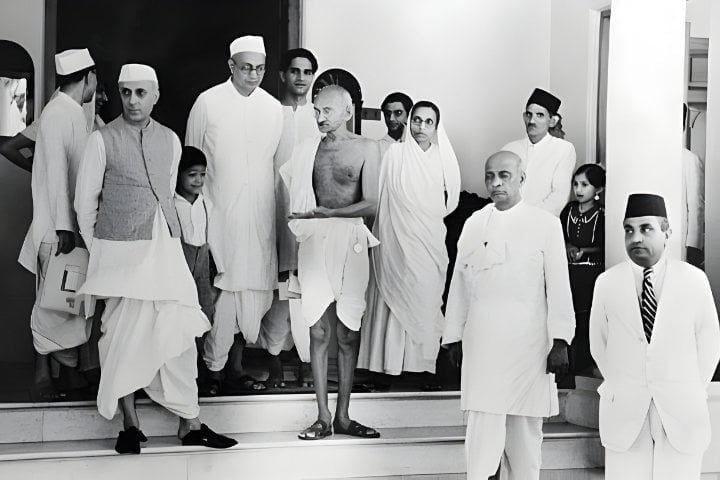

The resistance of India against British authority was not an abrupt uprising but rather a gradual and intensified effort led by various leaders and movements. Since the early 20th century, there has been a notable increase in resistance, particularly under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi.

The call to independence garnered increased momentum during the period of the non-cooperation movement (1920s) and civil disobedience movement (1930s). However, the call to “Quit India” by Congress from early August 1942 to September 1944, pushed India towards its ultimate freedom call.

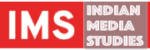

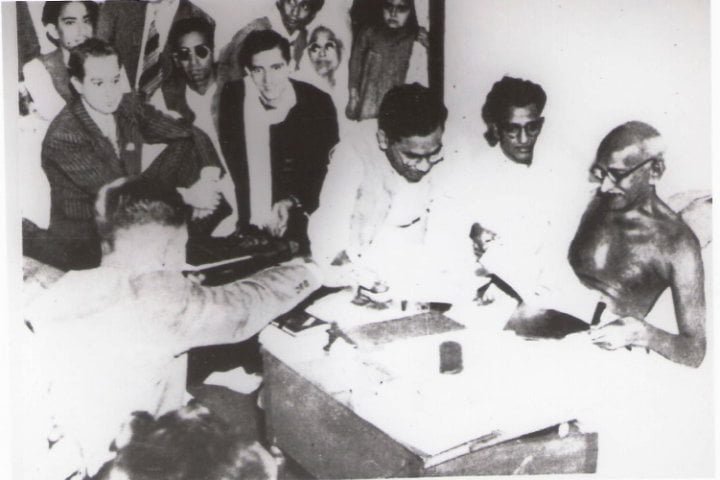

When Gandhi signed the “Quit India” resolution at the Gowalia Tank Maidan (now August Kranti Maidan) in Bombay, it was the loudest and greatest call for the British to leave India once and for all. “Quit India” and Gandhi’s call to “do or die” sent strong messages to the people.

The Catalysts of the Movement

The Quit India resolution was a measured response to Britain’s involvement in the Second World War and its attempts to get unconditional Indian support in the war. In exchange for their backing, Congress wanted full independence.

Because Indians were only partially supportive of the war effort, the British government sent a team to India in March 1942 under the leadership of Stanford Cripps, the speaker of the House of Commons. The Cripps Mission’s goal was to talk with INC leaders about terms for full cooperation in the war in exchange for giving some of the Viceroy’s powers to an elected Indian assembly.

However, Congress disagreed with the Cripps Mission’s terms and wanted a timetable for self-government. Gandhi said the Cripps Mission’s offer is like “a post-dated cheque on a crashing bank.”

The Launch of Quit India Movement

The Resolution and Its Significance

On July 14, 1942, the Congress working committee at Wardha urged complete independence or massive civil disobedience. The resolution said, “In order to defend India’s inalienable right to freedom and independence, the committee hereby approves the commencement of a mass nonviolent struggle on the largest possible scale, so that the country may utilize all the nonviolent strength it has built up over the last 22 years of peaceful struggle.”

Gandhi’s “Do or Die” Speech

Gandhi gave his “Quit India” speech on August 8, and the next day, he was arrested along with almost the entire Congress leadership. During the August 1942 protests, Gandhi reportedly said, “We shall either free India or die in the attempt, we shall not live to see the perpetuation of our slavery.”

The Movement Unfolds

Initial Reactions and British Clampdown

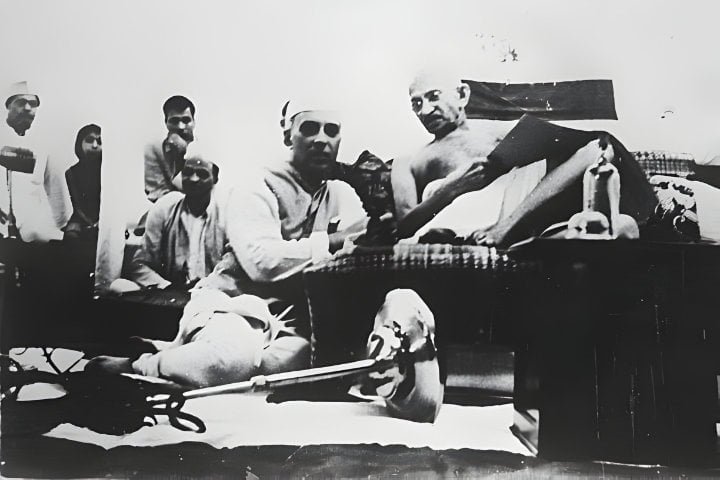

The British government responded swiftly and harshly, resulting in the killings of hundreds during the protests. By August 9, Gandhi and the Congress leadership were arrested, leading to widespread protests and acts of civil disobedience across the country.

There was a strong gap in communication between the leadership and the masses after their detention. The outcome was a mass-driven campaign with some of the most brazen defiance in the history of the independence movement.

Government institutions were targeted, telegraph wires were cut, and railway stations were set ablaze in symbolic defiance against British rule.

The Role of the Masses

With the leadership detained, the movement truly became a people’s struggle. Ordinary citizens stepped up, organizing rallies, and demonstrating significant resilience even in the face of severe repression. Women and children notably played a more active role than ever before, highlighting the inclusive nature of the movement.

Political Dynamics and Opposition

Another key point of the movement was the significance of large-scale political demonstrations. Ram Manohar Lohia, wrote to former governor-general of India Viceroy Linlithgow that at least 20% of the country’s people joined the movement, reflecting how determined they were to become independent.

However, not all were in favor of the Quit India Movement. Groups like the Muslim League, Hindu Mahasabha, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and the Communist Party of India expressed their reservations and, in some cases, outright opposition. These divisions underscored the complex political landscape of India during this period.

Conclusion

The Indians were firm in their beliefs and unwilling to give up, even though they did not have the political or military power to defeat the British.

Although the movement did not force an immediate British withdrawal, it severely undermined British authority and demonstrated India’s determination for freedom. The movement’s intensity and widespread participation showcased the depth of Indian nationalism.

The Quit India Movement significantly weakened the British hold on India and laid the groundwork for the post-war independence movement. It is widely credited with bringing India to the brink of independence, which was finally achieved in August 1947.

The Quit India Movement is a testament to the power of mass mobilization and non-violent resistance. Indians felt a sense of unity and national identity through the movement, which went beyond social, cultural, and religious differences. It also sped up the process of independence. In India’s history, it was a turning point.

The CUET UG Mass Communication syllabus contains this topic under the Communication section.