- 8 Ways Marxist Theory Shapes Contemporary Media Studies

- Analysis of Marxist View on Media

- 10 Revolutionary Marxist Literature That Changed History

Marxist Theory of Media

The Marxist Theory of Media provides a critical view of how media interacts with power structures and ideology in capitalist societies based on Marxist philosophy and critical theory.

In This Article

Marxist approaches to media are essential for UGC-NET aspirants. They offer insights into the political economy of media, the ideological functions of mass communication, and the media’s role in upholding or challenging social hierarchies.

This theoretical framework is relevant in India due to its complex media landscape, diverse socio-economic conditions, and ongoing media ownership and control debates. This exploration will focus on key ideas, applications, strengths, weaknesses, and the relevance of Marxist theory of media in the Indian media and communication context.

Key Scholars of Marxist Theory for Media

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels did not create a specific media theory. Still, they established the groundwork for Marxist media analysis through their critique of capitalist society and their ideas on ideology, class struggle, and the connection between economic base and superstructure. Their work offers a crucial perspective for analyzing the media’s role in society and its connection to power structures.

Marx and Engels’ contribution is central to the concept of base and superstructure. This model declares that society’s economic base, made up of the means and relations of production, is the foundation for the superstructure, including institutions such as media, education, and culture.

According to this view, media reflects and reinforces the economic base as part of the superstructure. This perspective examines how the economic structures of capitalist society affect media ownership, production, and content.

Marx and Engels’s concept of ideology is important for analyzing media. They argued that the ruling ideas in any society are the ruling class’s ideas. Media institutions, typically owned or controlled by powerful economic interests, often produce and circulate ideas that support the interests of the dominant class.

This concept has played a key role in shaping critical approaches to media content analysis, prompting scholars to investigate how media narratives may normalize and justify existing power dynamics.

Class struggle, a key concept in Marxist thought, informs media analysis. Marx and Engels argued that conflicts between social classes with opposing interests shape history.

This concept encourages an analysis of how various class interests are represented in media content, the role of media in ideological conflict, and the stratification of access to media production and consumption based on class.

Marx and Engels’ critique of commodity fetishism provides a basis for analyzing media as commodities in capitalist societies. This perspective encourages an examination of how media commodification affects content production, distribution, and consumption, potentially alienating both producers and consumers.

In India, Marxist foundations provide a useful perspective for examining different elements of the media landscape. For instance, one might examine how the ownership patterns of major media outlets in India reflect broader economic power structures or how media narratives around issues like economic development or social inequality align with or challenge dominant class interests.

The concept of ideology could be used to critically analyze how Indian media represents issues related to caste, class, or regional disparities.

Marx and Engels did not directly discuss modern mass media, but their concepts regarding economic structures, power, and ideas have been essential for later Marxist media theorists.

Their work offers a framework for understanding media as a key component of society’s ideological and economic structures rather than a neutral source of information. This perspective remains relevant for analyzing current media phenomena, including media ownership concentration and the ideological content of news and entertainment in India and worldwide.

Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Gramsci was an Italian Marxist philosopher and politician who significantly influenced Marxist theory, media studies, and cultural analysis. His concept of cultural hegemony, in particular, has been instrumental in shaping Marxist approaches to understanding media’s role in society.

Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony built on Marx’s concepts of ideology and class struggle, highlighting the role of culture and civil society in sustaining power structures.

He claimed that the ruling class sustains its dominance through economic and political control as well as cultural leadership. The subordinate classes must accept the ruling class’s worldview as natural and inevitable to achieve this leadership.

Gramsci’s ideas indicate that media institutions are essential in creating and sustaining cultural hegemony. According to this perspective, media often serve as vehicles for disseminating the ideas, values, and beliefs that support the existing social order.

However, Gramsci’s theory also recognizes that hegemony is never complete or stable; it must be constantly negotiated and renegotiated. This allows counter-hegemonic forces to challenge dominant narratives using alternative media practices.

Gramsci’s concept of “common sense” is particularly relevant to media analysis. He argued that hegemony works by shaping what is considered common sense in society—the taken-for-granted assumptions that guide everyday thinking.

Media significantly construct and circulate common-sense notions that often align with the interests of dominant groups. This insight has led media scholars to examine how seemingly neutral or objective media content can reinforce existing power structures.

Another key contribution of Gramsci is his concept of the “war of position.” The war of position is a long-term struggle for ideological and cultural dominance within civil society, unlike the direct confrontation seen in a “war of maneuver.”

This refers to the ongoing struggle for control over how meaning is produced and shared across different media channels. This concept has significantly shaped our understanding of how alternative and activist media challenge dominant narratives.

Gramsci’s ideas can be used in India to examine how mainstream media reflect and reinforce dominant ideologies related to economic development, nationalism, and social hierarchies.

One might analyze how media narratives regarding India’s economic growth or modernization correspond with specific class interests, or how media representations of caste and religion help sustain certain power structures.

Gramsci’s work also emphasizes the role of intellectuals in either maintaining or challenging hegemony. This viewpoint has shaped the examination of journalists, media professionals, and cultural producers as possible agents of social change or as supporters of the status quo.

In India, this may include analyzing how prominent media figures influence public discourse on important social and political issues.

Gramsci’s acknowledgment of popular culture’s role in hegemonic processes has significantly impacted media studies. This has led to analyses of how forms of entertainment media, from Bollywood films to television soap operas, might function to reinforce or occasionally challenge dominant ideologies.

Gramsci’s contributions have encouraged a more nuanced understanding of media power that goes beyond simple notions of propaganda or direct control.

His work shows how media are involved in cultural and ideological processes and acknowledges the potential for resistance and change within these systems. This perspective is useful for analyzing how media shapes social realities and power relations in India and beyond.

Louis Althusser

Louis Althusser, a French Marxist philosopher, significantly contributed to Marxist theory, influencing media studies and cultural analysis.

His work on ideology and the concept of Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs) has been particularly influential in shaping Marxist approaches to understanding media’s role in society.

Althusser’s theory of ideology expanded on Marx’s ideas by emphasizing the material existence of ideology in social practices and institutions. He argued that ideology is not just a collection of ideas or false consciousness; it is a lived relationship with the world that influences how individuals perceive their role in society.

This perspective has important implications for media studies, showing that media not only reflect ideological content but also shape subjects within those frameworks.

He identified several institutions, such as media, education, religion, and family, as ISAs that operate mainly through ideology to reproduce the conditions of production in capitalist societies.

In this framework, media are viewed as a crucial ideological state apparatus that interpellates individuals as subjects within the dominant ideology. Interpellation is the process by which ideology “hails” individuals and shapes them as subjects. This concept is influential in media studies, offering a method to analyze how media engage their audiences and place them within particular ideological frameworks.

Althusser’s work highlights the superstructure’s relative autonomy, including media, from the economic base. He argued that the economic base determines the superstructure, but also noted that the superstructure has its own logic and can influence the base.

This view enables a detailed analysis of media institutions and their connections to economic and political power structures.

Althusser’s ideas in media analysis prompt an examination of how media practices and content reproduce dominant ideologies and social relations.

This may include examining how news formats, entertainment programs, or advertising methods engage viewers as specific types of subjects, such as consumers, citizens, or members of certain social groups. This raises questions about how media institutions operate as places for producing and reproducing ideology.

Althusser’s concept of overdetermination is also relevant to media studies. This theory suggests that multiple interrelated causes influence social phenomena instead of a single decisive factor. Media analysis examines the complex interactions of economic, political, cultural, and technological factors that influence media production, content, and reception.

Althusser’s theories can be applied in India to analyze how different media forms—news broadcasts, Bollywood films, and social media—act as ISAs, reproducing and occasionally challenging dominant ideologies related to nationalism, economic development, and social hierarchies.

One could examine how television news positions viewers as specific national subjects or how advertising in India shapes individuals as consumers in a capitalist system.

Althusser’s work has influenced the understanding of how media reproduces social inequalities. This perspective can be used in India to analyze how media representations and practices contribute to the reproduction of caste, class, or gender hierarchies.

Althusser’s theories have faced criticism for possibly exaggerating ideology’s power and minimizing individual agency. However, his work remains useful for analyzing the intricate connections between media, ideology, and social reproduction.

His contributions have prompted media scholars to explore deeper structures and processes that influence how media shape our understanding of the world and our role in it.

This perspective is useful for analyzing current media phenomena in India and worldwide, especially in understanding how media systems uphold or contest existing power relations.

The Frankfurt School (Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse)

The Frankfurt School, especially through Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse, significantly contributed to the Marxist theory of media by developing critical theory and applying it to mass media and culture analysis.

Their work, arising from Nazi Germany and later post-war consumer capitalism, provided a deep critique of the media’s role in modern society.

The idea of the “culture industry,” which Adorno and Horkheimer developed in their seminal work “Dialectic of Enlightenment,” is central to the Frankfurt School’s contribution. They asserted that mass media and popular culture had become industrialized, producing standardized cultural products that influenced the masses towards passivity and conformity.

According to this view, the culture industry, including film, radio, and magazines, creates false needs and maintains the dominance of capitalist ideology by promoting a culture of consumption and entertainment that distracts people from their true needs and potential for critical thinking and social change.

The Frankfurt School scholars were particularly concerned with how the culture industry contributed to the erosion of individual autonomy and critical consciousness.

They argued that the standardization and mass production of cultural goods led to a homogenization of consciousness, making it difficult for individuals to imagine alternatives to the existing social order.

The criticism concentrated on how the media presents information, indicating that commodification and entertainment shape news and educational content.

Herbert Marcuse’s concept of “one-dimensional man” further developed this critique. He claimed that advanced industrial society and its media create false needs that connect individuals to the current system of production and consumption.

Marcuse argued that this process flattens discourse and eliminates critical, opposing viewpoints, making genuine critique increasingly difficult in society.

The Frankfurt School’s analysis also emphasized the role of technology in shaping social relations and consciousness. The text acknowledges technology’s potential for human freedom but critiques its use in capitalist societies.

This critique of technology has important implications for media theory, prompting an examination of how media technologies influence communication and social interaction.

The Frankfurt School’s work in media studies encourages a critical look at media content, production processes, and audience reception. It encourages scholars to look beyond surface-level messages to consider how media structures and practices might reinforce dominant ideologies and social relations.

This approach has been influential in developing critical media literacy, emphasizing the importance of cultivating the ability to critically analyze and resist mass media’s manipulative aspects.

The Frankfurt School’s contributions also highlight the importance of considering the political economy of media. Their work encourages analysis of how media ownership structures and economic imperatives shape content production and distribution, potentially limiting the diversity of perspectives and reinforcing existing power structures.

The Frankfurt School’s ideas can be used to analyze different aspects of the media landscape in India. For instance, one might examine how the commercialization of Indian media, particularly in the post-liberalization era, has affected content diversity and quality.

The concept of the culture industry could be used to critically analyze the role of Bollywood or television entertainment in shaping cultural norms and consumer behaviors. Additionally, their critique of technological rationality could inform analyses of how digital media platforms in India might reshape social relations and communication patterns.

While the Frankfurt School’s theories have been criticized for being overly pessimistic and potentially elitist in their view of popular culture, their work provides valuable tools for critical media analysis.

Their emphasis on the ideological functions of media, the impact of commercialization on cultural production, and the potential of media to shape consciousness remains relevant in understanding contemporary media phenomena, both in India and globally.

The Frankfurt School’s contributions remind us of the importance of maintaining a critical stance towards media systems and their role in society. They encourage ongoing examination of how media might both reinforce and potentially challenge existing power structures and social relations.

Raymond Williams

Raymond Williams was a Welsh academic, novelist, and critic who significantly contributed to the Marxist theory of media, focusing on cultural materialism and the relationship between culture, society, and media.

Williams connected Marxist theory to cultural studies, providing a nuanced and historically informed analysis of media and cultural production.

Central to Williams’ contribution is his concept of cultural materialism, which sought to understand cultural practices, including media, as material processes embedded in specific historical and social contexts.

This approach built on traditional Marxist base-superstructure models by highlighting the active role of culture in social life. For Williams, media and other cultural forms were not simply reflections of an economic base but were integral to the whole social process.

Williams introduced the concept of “structures of feeling” to describe the lived experience of culture at a particular time and place. This concept has significantly impacted media studies, prompting analysts to examine how media reflect and shape collective experiences, attitudes, and sensibilities.

In the Indian context, this could be applied to examine how media forms like Bollywood cinema or television serials capture and contribute to evolving social attitudes and experiences in a rapidly changing society.

His television work, especially in “Television: Technology and Cultural Form,” provided a detailed analysis of the medium that surpassed basic technological determinism.

According to Williams, complex social, economic, and cultural factors—not just technological innovation—impacted the development of television. This perspective promotes a detailed examination of media technologies, considering how social practices and cultural forms affect them and are also affected by them.

Williams developed the concepts of residual, dominant, and emergent cultures, offering a framework for understanding how media interact with traditional cultural forms, current mainstream culture, and new cultural expressions.

This framework is relevant in India, where media navigate traditional cultural values, dominant narratives, and global influences.

His critique of “masses” in mass media and culture questioned simplistic ideas about a passive audience. Williams highlighted the complexity and diversity of cultural experiences, as well as the active role of individuals and communities in shaping and interpreting culture.

This viewpoint has shaped methods in audience studies and reception theory within media research.

Williams analyzed advertising as the “official art of capitalist society,” providing a critical view of how commercial media influences desires and social relationships. His insights are important for understanding how advertising influences consumer culture and social values in modern India.

Williams’ approach can be used to examine how different media forms balance local, national, and global cultural influences in India. His framework can be used to analyze how Indian television and digital media platforms integrate traditional cultural elements while adapting to global media trends.

Williams’ emphasis on the importance of access to and control over means of communication as a key aspect of cultural democracy continues to be relevant in discussions about media ownership, digital divides, and the democratization of media in India and globally.

His idea of “mobile privatization” explains how broadcasting technologies enable a type of privatized mobility, allowing experiences of other places while staying in home environments. This concept is useful for analyzing current media consumption trends, especially with smartphones and digital media.

Raymond Williams’ contributions to the Marxist theory of media provide a more nuanced and culturally sensitive perspective on the role of media in society. His work promotes an examination that takes into account the intricate relationships among media technologies, cultural practices, economic frameworks, and social experiences.

This perspective remains valuable for media scholars and practitioners in India, offering tools to critically examine the evolving media landscape in its specific historical and cultural context while also considering broader global trends and influences.

Stuart Hall

Stuart Hall, a Jamaican-born British cultural theorist and sociologist, made significant contributions to the Marxist theory of media through his work in cultural studies and his analysis of representation, ideology, and the active role of audiences in media consumption.

Hall’s work enhanced Marxist approaches to media, providing a clearer understanding of how meaning is created, shared, and understood in media texts.

Central to Hall’s contribution is his encoding/decoding model of communication, which challenged linear, sender-receiver models of media effects. This model suggests that producers ‘encode’ media messages based on specific ideological frameworks, which audiences then ‘decode,’ potentially interpreting these messages in different ways.

Hall identified three potential positions for decoding:

- the dominant-hegemonic position (accepting the message as intended),

- the negotiated position (partially accepting the message while adapting it to one’s context), and

- the oppositional position (rejecting the intended meaning and interpreting it contrary to that)

This model highlights how audiences actively create meaning from media texts and acknowledges the possibility of varied interpretations influenced by cultural, social, and individual factors.

Hall’s analysis of representation in media was influential, focusing on how media constructs and circulates representations of various social groups.

He stated that representation is not just a reflection of reality; it is an active process of meaning-making with real social and political consequences.

This perspective is valuable for analyzing media representations of race, class, and identity, promoting a critical examination of the power dynamics in media representation.

Hall expanded on Gramsci’s concept of hegemony by introducing the idea of articulation in media and cultural analysis. This concept examines the connections between various elements, such as ideas, social practices, or cultural forms, to generate meaning and ideological effects.

Hall’s approach to articulation allows for a more flexible and contextual understanding of how media texts operate within broader cultural and social structures.

Hall’s work highlighted the need to consider historical and cultural context in media analysis. He opposed universal or ahistorical theories of media effects, emphasizing the importance of understanding media processes within their specific social, cultural, and historical contexts.

This viewpoint has been essential in creating more nuanced and culturally sensitive methods in media studies.

Hall’s analysis of how news is socially produced significantly impacted the news media landscape. He examined how news organizations choose, frame, and present information, arguing that institutional practices, cultural assumptions, and power dynamics influence this process.

This work has been vital in shaping critical news analysis methods and understanding the media’s role in constructing social reality.

Hall significantly contributed to analyzing popular culture through a Marxist lens. He advocated for seriously considering popular culture as a battleground for ideology, analyzing its role in supporting and contesting dominant power structures.

This perspective has influenced approaches to studying various media forms, from television to music to digital media.

Hall’s theories can be used to analyze different aspects of the media landscape in India. For instance, his encoding/decoding model could be used to examine how different audiences in India interpret Bollywood films or news broadcasts, considering how factors like class, caste, region, or language might influence these interpretations.

His work on representation can guide analyses of how Indian media portrays various social groups or issues such as caste, gender, and regional identities.

Hall’s emphasis on the importance of identity in cultural processes is particularly relevant in the diverse Indian context. His insights can be used to analyze how media in India shape and negotiate different cultural and national identities.

Overall, Stuart Hall’s contributions to the Marxist theory of media offer a more dynamic, culturally nuanced approach to understanding media’s role in society. His work promotes analysis of the complex relationships among media production, text, and reception, all within specific historical and cultural contexts.

This perspective is important for media scholars and practitioners in India, providing tools to critically analyse the changing media landscape, focussing on power, representation, and cultural identity.

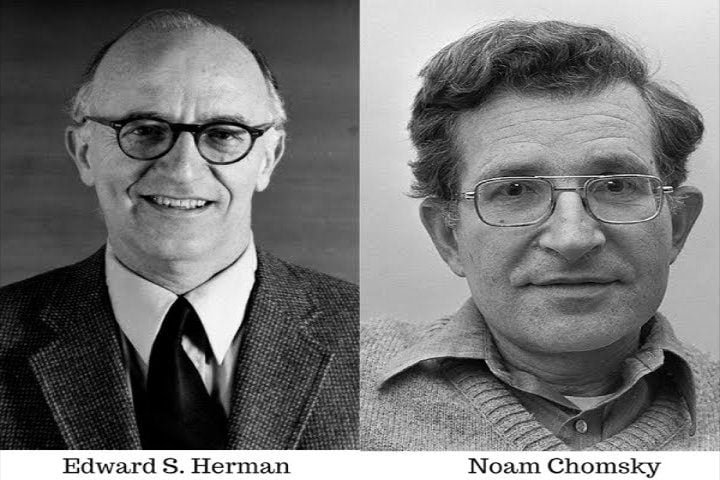

Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman

Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman contributed to the Marxist theory of media by developing the propaganda model, which critically analyses the functioning of mass media in capitalist societies.

Their seminal work, “Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media,” published in 1988, presents a structural critique of the media system, particularly focusing on the United States but with broader implications for understanding media in capitalist democracies worldwide.

Chomsky and Herman’s propaganda model indicates that mass media generate “manufactured consent” for the agendas of privileged groups that dominate society and the state.

This occurs not via direct censorship but through five filters that influence news content: ownership, advertising, sourcing, flak, and anti-communism, which was later expanded to encompass dominant ideologies.

The first filter, ownership, shows how media ownership concentration among large corporations affects content. Chomsky and Herman state that the profit-driven nature of these corporations and their connections to other influential entities influence the overall direction of news and analysis.

This can be used to analyse how ownership patterns of major media outlets in India affect their coverage of economic and political issues.

The second filter examines how the media’s dependence on advertising revenue influences content. Media outlets prioritise advertisers’ interests, which may distort content to foster a “buying mood” and steer clear of subjects that could unsettle potential consumers.

This perspective could be used to analyze how advertising dependencies shape content in Indian media, particularly in the context of the country’s growing consumer economy.

The third filter, sourcing, looks at how the media’s reliance on information from primary sources and agents of power like the government, business, and “experts” funded and approved by them shapes news content.

This filter is particularly relevant in analyzing how Indian media cover political and economic issues, often relying heavily on official sources.

The fourth filter, flak, indicates negative reactions to media statements or programs. Chomsky and Herman state that powerful entities can create flak, which disciplines the media and discourages coverage of specific topics or viewpoints.

This can analyze how different pressures, such as government criticism and social media backlash, affect media coverage in India.

The fifth filter, initially termed anti-communism but later expanded to cover dominant ideologies, examines how these ideologies influence media discourse.

This can be used to analyze how dominant narratives about nationalism, economic development, or social issues affect media coverage in India today.

Chomsky and Herman highlight that media bias is systemic, arising from structural factors in the media system rather than individual journalists’ choices.

This results in a restricted debate, as the media showcases a narrow set of perspectives that mainly reflect the interests of influential groups.

The Propaganda Model has been influential in encouraging critical analysis of media systems and content. It provides a framework for examining how media might reinforce existing power structures and limit the range of perspectives presented to the public.

This model can be used to analyze different aspects of the media landscape in India, including economic policy coverage and the representation of marginalized groups.

The Propaganda Model has been criticized for possibly exaggerating media uniformity and downplaying journalistic agency and audience resistance, yet it continues to be an effective tool for critical media analysis.

The focus on structural factors and the political economy of media remains important for understanding media systems in capitalist societies, particularly in India’s growing commercialized and globalized media landscape.

Chomsky and Herman’s work prompts a closer look at the influences on media content and the constraints of mainstream media in offering varied viewpoints.

Scholars and practitioners in India can use these insights to analyze the country’s changing media landscape and understand how structural factors may affect public discourse in the world’s largest democracy.

Dallas Smythe

Dallas Smythe made significant contributions to the Marxist theory of media through his work on the political economy of communication, particularly with his concept of the “audience commodity.” Smythe’s approach shifted the focus of media analysis from content to the economic structures underlying media production and consumption.

Smythe argues that the main commodity of mass media is audiences, not content. He suggested that media companies create audiences and sell them to advertisers.

This view questions the conventional idea of media as just content creators and prompts a closer look at the economic ties that support media systems.

Smythe’s “audience commodity” concept indicates that media audiences engage in unpaid labor by viewing advertisements and consuming media content.

He argued that this labor generates value for advertisers by influencing consumer demand and aiding in the reproduction of labor power. This perspective expands the Marxist analysis of labor and commodification to media consumption, providing insight into capitalism’s function within media systems.

Furthermore, Smythe developed the idea of the “consciousness industry,” arguing that media play a crucial role in shaping public consciousness to serve capitalist interests.

He argued that media, via advertising and programming, creates and sustains a consumer culture that upholds the capitalist economic system.

Smythe’s work also emphasized the importance of analyzing the entire communication process, including production, distribution, and consumption, within its broader political and economic context.

This holistic approach has been influential in developing more comprehensive analyses of media systems and their role in society.

Smythe’s theories can be used to analyze the impact of media commercialization in India, especially after liberalization, on the dynamics between media companies, advertisers, and audiences.

His concept of the audience commodity could be used to analyze how Indian media markets segment and sell their audiences to advertisers, especially in the context of targeted digital advertising.

Smythe’s work also provides a framework for analyzing the role of media in promoting consumerism in India’s growing economy. His insights could be used to examine how media content and advertising work together to shape consumer desires and behaviors in the Indian market.

Moreover, Smythe’s emphasis on the economic structures underlying media can inform analyses of media ownership and control in India, encouraging examination of how these structures influence content production and distribution.

While Smythe’s theories have been criticized for potentially oversimplifying the complex relationships between media producers, audiences, and advertisers, his work continues to provide valuable insights for critical media analysis.

His emphasis on the economic aspects of media systems provides an important viewpoint for understanding the forces influencing media in capitalist societies, including India’s changing media landscape.

Smythe’s contributions remind us of the importance of considering the economic underpinnings of media systems when analyzing media content and effects.

His work provides scholars and practitioners in India with tools to critically examine the commercialization of media, the role of advertising, and the commodification of audiences in the country’s diverse and rapidly changing media landscape.

Conclusion

the Marxist theory of media, with its various elements and changing viewpoints, is an important framework for critical media analysis. Understanding these theories is crucial for exam success and for grasping the complex relationship between media, power, and society in India.

Marxist approaches provide useful tools for analyzing Indian media, including ownership patterns, ideological content, digital divides, and cultural representations. While these theories have limitations and face ongoing critiques, they continue to provide insightful perspectives on the role of media in shaping social realities and power relations.

In an era of rapid technological change, media convergence, and global information flows, Marxist Media Theory’s insights into the political economy of communication and the ideological functions of media remain highly relevant. These theories remind us to look beyond surface-level content and consider the deeper structures and power dynamics that shape media systems and their societal impacts.

UGC NET Preparation Tips

1. Learn the main ideas and contributions of each significant scholar in the Marxist theory of media.

Understand how various Marxist approaches can be used to analyze different aspects of Indian media.

3. Compare and contrast various Marxist perspectives on media.

4. Analyze potential critiques or adaptations of Marxist theories considering India’s distinct media landscape and cultural context.

5. Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of Marxist approaches to understanding modern media issues in India and worldwide.